Spaciousness of Bass: Is Stereo Bass a Myth or Reality?

Stereo Bass: What exactly is it?

Stereo bass is a topic of much debate among the audiophile community for decades. Many proponents argue that stereo bass is necessary to accurately reproduce the original musical event. This entire article started as a conversation with one of the leading advocates for stereo bass, Dr. David Griesinger. Dr. Griesinger is a leading expert in performance hall acoustics, a principal engineer at Lexicon, and an ardent classical music lover. After months of correspondence and experimentation with David’s help, I walked away with a newfound appreciation for stereo bass. Yet what exactly is stereo bass? How do we hear it? What does it sound like? Why would it be important, if at all?

Stereo vs Mono Bass YouTube Video Discussion

Let’s start this discussion by first describing what I think is a common understanding of stereo bass. Stereophonic sound is the reproduction of music through two or more sound sources with the intent of fooling the brain into perceiving sound as coming from a multidimensional space. It’s a recreation of reality. This gives the impression that stereo bass is about recreating the original sound source location at low frequencies. In other words, if stereo is about using two or more speakers to recreate the original musical experience, then stereo bass is preserving this multidimensional sound experience at low frequencies.

So here is the problem. This definition often gives the impression that we are talking about the imaging or panning and placement of musical instruments across an imaginary soundstage. The above definition is correct, but how this pertains to stereo bass is different from what I had previously thought, and I suspect is true for our readers. This multidimensional space has other properties besides just our ability to hear instruments as coming from in front of us. The room in which the performance takes place is perceivable as well. When we walk into any musical venue (or any space for that matter) the way in which sound reflects around that room tells us a lot about that room. It tells us how large it is, how lively it is, where we are relative to the walls, floor, and ceiling, as well as where the musicians are relative to us, the walls, floor, and the ceiling. Two aspects of how our brain perceives this have been given formal terms known as envelopment or spaciousness and apparent source width. Apparent source width gives us a sense of scale for a musical performance and is largely driven by the lateral reflections in the performance. Spaciousness or envelopment is the subjective immersion of the listener in the performance. Both of these properties are critical aspects of how we perceive the performance as subjectively real yet have nothing to do with simpler definitions of imaging such as apparent source location, or where the musicians are placed in the room.

Let’s not call it stereo bass anymore, it seems a term coined by Todd Welti, Bassiousness (base-shush-ness), is more fitting. Stereo bass is not about our ability to place the apparent location of an instrument at low frequencies, it is about a sense of envelopment or spaciousness at low frequencies. When the effect is present, it is what allows bass to sound like it is coming from outside our head. When bass is monophonic (such as is the case with most bass managed systems), bass tends to sound like it is coming from inside our head.

The Problems with Bassiousness

From reading the last section of this article, many would conclude that bassiousness is desirable, and as such, all systems should be optimized for this. Life is not so simple. First, bassiousness is subtle when present in real music or movies. When I first experienced this bassious effect, I didn’t find it as apparent as I had expected. Additionally, I wouldn’t say the effect was better. Instead, I would just call it different. The effect is best described as reminiscent of what it sounds like when you change the phase back and forth for pink noise. It creates a shift from sounding like it is in your head to arrival from all around you. I could see this effect as being most desirable with certain musical types such as large orchestral recordings or intimate jazz recordings. In these scenarios, the musical event, the venue play into the experience.

Another problem, besides the subtlety of the effect, is that not all musical recordings contain the stereo encoding at low frequencies needed for the bassiousness effect to happen. In general, low frequencies in most recordings are highly correlated, meaning monophonic. David Griesinger is one of the biggest proponents of this effect and designed the famed Lexicon 224. Any recording that uses the lexicon reverb units should have proper stereo bass as long as no later processing was done to remix the low frequencies to mono. In general, low frequencies in most recordings are highly correlated, meaning monophonic.

Finally, the effect is easily disturbed. Reading the articles that David Griesinger has written on stereo bass and spaciousness makes clear that the effect is heavily influenced by the low-frequency modes in the room. Certain modes, such as those that come from the sidewalls, are critical. Others, such as those that are caused by floor and ceiling reflections are detrimental. What this means in practice is that the placement of speakers and subwoofers in the room and the acoustics of the room play into the audibility of this spatial effect. My experience with the acoustical issues is that it can be tricky to set up correctly and is easily disturbed. Rooms with acoustic false ceilings tend to absorb most of the vertical modes and the effect is easier to hear. In more traditionally constructed rooms, this is not true. The difficulty I had in setting systems up to hear this effect mixed with the overall subtle nature of the effect was very frustrating and lead to my ultimate abandonment of this concept.

How do you maximize the stereo bass effect?

There are tricks to helping ensure that this effect can be heard. The effect is largely driven by lateral reflections and the modes formed by these lateral reflections. This suggests that maximizing the lateral separation of the low-frequency sources can help ensure the effect is properly created. Placing the speakers wider apart than may normally be optimal, such as near the corners of the room, can be one trick to help enhance this effect. Another trick is to place subwoofers on either side of the listener along the sidewalls. In both cases, the large lateral separation and placement in a pressure maximum for the lateral modes lead to a better chance of hearing the effect. Finally, consider treating the ceiling in a manner to absorb low frequencies. Acoustic false ceilings are great for listening rooms, they are acoustically ideal, as they absorb a significant amount of low frequencies, eliminating the vertical modes. For traditionally constructed ceilings, an alternative would be to apply bass traps to much of the ceiling. Not practical you say? Who said good sound was practical?

Another consideration is that the spatial enhancement of low frequencies has a lower limit. Its exact lower limit is not certain as research has drawn conflicting results. The lower limit likely falls somewhere between 50hz and 90hz. In any case, it suggests that bass managing below the lower limit won’t negatively impact the spatial effect. The problem is that the area in which multiple subwoofers tends to make the biggest difference is in the upper range of the subwoofers, between 50hz and 100hz. Some might argue that bass managing below 50-60hz is a good safe solution. Dr. Floyd Toole has argued that 80hz is fine as it falls into the range that some of the more recent research suggests is the lower limit of this effect. One concern I have with Toole’s suggestion is that there is still a significant overlap between the monophonic subwoofer and stereo mains. I worry this overlap could lead to significant disruption of the effect.

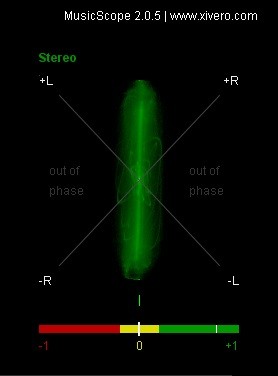

MusicScope Analysis of John Williams Jurassic Park Theme recording with low pass filter applied at 200hz. Indicates significant stereo content below 200hz.

Note the existence of positive and negative phase left and right content.

To Be, or Not to Be, That is the Question?

To set up for stereo bass or to setup fo r proper bass management; that is the choice in front of us. Unfortunately, it is not possible to have both. Properly bass managing a system so that multiple subwoofers can be used to improve spatial consistency and flatness require that all the low-frequency sources are correlated. There cannot be temporal-spatial variation. On the other hand, stereo bass is defined as there being temporal-spatial variation. This largely gives us a binary choice to make, stereo bass, or smooth bass. Furthering this problem, the best placement of speakers for a flat and consistent amplitude response typically does not match the optimal locations for maximum lateral separation or excitation of lateral modes. The choice is based on which set of compromises is a better fit for your listening preferences. It is my opinion that smoothness and consistency in the amplitude response are more important than the spaciousness afforded by stereo bass. Given the choice here, I believe that it is better to stick to a mono bass system characterized by multiple mono bass sources spread throughout the room and crossed over at around 80hz. After experimenting with this concept and sharing it with other Audioholics, my end conclusion is that Floyd Toole is probably right. I say this with the utmost respect for David Griesinger and with the firm belief that he is generally correct in many of his assertions.

r proper bass management; that is the choice in front of us. Unfortunately, it is not possible to have both. Properly bass managing a system so that multiple subwoofers can be used to improve spatial consistency and flatness require that all the low-frequency sources are correlated. There cannot be temporal-spatial variation. On the other hand, stereo bass is defined as there being temporal-spatial variation. This largely gives us a binary choice to make, stereo bass, or smooth bass. Furthering this problem, the best placement of speakers for a flat and consistent amplitude response typically does not match the optimal locations for maximum lateral separation or excitation of lateral modes. The choice is based on which set of compromises is a better fit for your listening preferences. It is my opinion that smoothness and consistency in the amplitude response are more important than the spaciousness afforded by stereo bass. Given the choice here, I believe that it is better to stick to a mono bass system characterized by multiple mono bass sources spread throughout the room and crossed over at around 80hz. After experimenting with this concept and sharing it with other Audioholics, my end conclusion is that Floyd Toole is probably right. I say this with the utmost respect for David Griesinger and with the firm belief that he is generally correct in many of his assertions.

References

Griesinger, David. 2005. " Loudspeaker and listener positions for optimal low-frequency." Audio Society of America. 2390-2391.