Sound Reproduction: Psychoacoustics of Loudspeakers and Rooms

People unversed in technical terminology will talk about an audio system’s 'sound quality,' and what they mean is how good does the system sound to them and how ‘accurate’ is it. But what constitutes ‘sound quality’ exactly, in a more precise and scientific sense? Many people have spent a great deal of time and money chasing the better end of ‘sound quality,’ but without an understanding of what ‘sound quality’ is, they are stuck in a blind search for something that simply sounds good to them that they happen to chance upon. A better definition of sound quality would serve as a guide post for those seeking audio nirvana, and I do not think one can find a better explanation of this criterion called ‘sound quality’ than Dr. Floyd E. Toole’s latest book, ‘Sound Reproduction: The Acoustic and Psychoacoustics of Loudspeakers and Rooms, 3rd Edition’. It is more than just an introduction to sound reproduction and sound quality; it is a comprehensive explanation of all of the components that add up to sound quality, and how that quality can be good or go wrong. The recently released 3rd edition is a major re-ordering and rewrite that is updated with much of the latest advances in research and technology on the subjects that are covered.

Understanding Psychoacoustics

The subtitle, "the Acoustics and Psychoacoustics of Loudspeakers and Rooms," touches on the chief components that determine the quality of the sound reproduction. Let's expand on that subtitle: 'acoustics' is the science of the pressure waves of air that we hear as sound, and the need for that in ascertaining good sound reproduction is obvious. It is a technical endeavor and therefore has to have some means of being quantified. But acoustics alone is not enough to determine sound quality; humans are not robots and do not hear in the same way that a microphone 'hears.' 'Psychoacoustics' is the science of how humans perceive sound. As its name suggests, psychoacoustics is the bridging of psychology (perception) and physical acoustics. Clearly, this area of research is needed if we wish to understand sound reproduction in an enjoyable or accurate way as a human activity. ‘Loudspeakers’ are the point where the content is reproduced as sound pressure waves, and so these devices are crucial in this enterprise. The 'Room' is as much a part of any sound system as any other component, since it is the interaction of the room with the loudspeaker that is what we hear and not the loudspeakers alone. We sense the pressure waves of air (acoustics) generated by the loudspeakers as those pressure waves are shaped by the room and perceive it as sound (psychoacoustics). The subtitle lays down the groundwork needed in order to understand the ingredients that add up to sound quality, and each of these ingredients is discussed with depth and clarity in ‘Sound Reproduction.’

Image of Dr. Floyd Toole's current LCR arrangement in his personal listening space includes two inverted Revel Salon2s (to put the sound image where it belongs) and a Voice2 center. Speakers are driven by Mark Levinson 536s amplifiers. The front projection screen is outlined. Note the room looks like an art gallery, not a home theater. Superb loudspeakers, multiple subs with SFM (no bass traps needed) and stealth acoustical treatments allow for excellent sound and aesthetics.

Dr. Toole’s research into discerning what makes for good sound quality has been a strong influence on the philosophy and purpose of Audioholics.com. He uses a scientific approach into apprehending what traits that a sound system should have to sound good to people and why it does sound good to them. One interesting finding of his research is that what many people think sounds good is also the same thing as accurate sound; that is, the closer that an audio system can reproduce the recording to its intended sound, ie. the more “neutral” it is, the better it sounds to more listeners. Perhaps this should not come as a surprise, but since so many of us know people who run the bass and treble cranked up in their audio systems for that extra ‘boom and sizzle’ in their music, one might have thought that a more commonly desired sound was something more exaggerated from the norm. Thankfully, for the sake of simplicity, this is not the case, and the research has shown the most desirable sound for most people is the same thing as the most accurate sound. Tone controls can be used to compensate for imperfect recordings, or to add “excitement” if desired, but the good thing is that they can be turned up, down and off. If you start with neutral loudspeakers all options are possible.

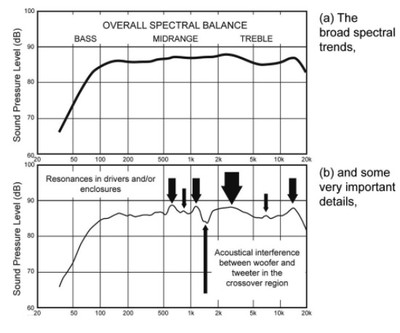

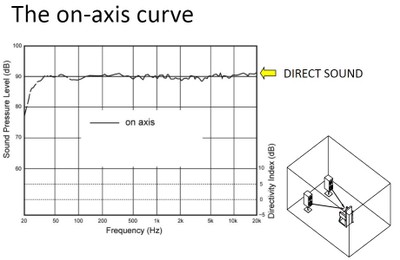

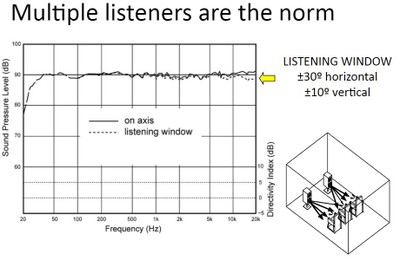

Since we have established desirable sound is also accurate sound, that simplifies the traits that our audio system must have to have good sound quality. It should reproduce the content as faithfully as possible. Perfect audio fidelity to the source content is impossible in real world conditions, but we should get as close as we can. The most important element that a sound system should have to maintain veracity to the source content is its frequency response. The frequency response is the amplitude a system reproduces different frequencies where the incoming signal has the same amplitude for all frequencies. A more relatable way to state that is frequency response is how evenly a system will reproduce all frequencies in the audible spectrum, from the deepest bass to the highest treble that humans can hear. The more evenly a system can playback sound at all frequencies, the more accurately it is able to reproduce the content of recordings. Dr. Toole’s research into the importance of frequency response for the human appreciation of sound reproduction has helped to give that aspect a scientific foundation where before it was merely thought to be a ‘good idea’ without much hard data to support the notion.

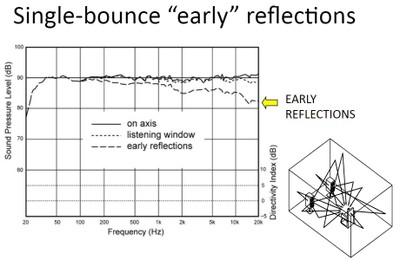

Since frequency response is of such paramount importance, a good deal of discussion in ‘Sound Reproduction’ is given to how we hear that response, what to look for in evaluating a system’s response, what the various frequency responses of a system can indicate, and so forth. This is critical stuff for evaluating the performance metrics of an audio system, and a deep understanding of it can allow one to know what an audio system can sound like simply from looking at a detailed set of its frequency response measurements.

Note the word ‘Loudspeakers’ in the subtitle of the book and the omission of the other components that make up an audio system: amplifier, preamplifier, source player, DACs, cables, and so on. The reason for this is the loudspeaker is going to affect the sound far more than the other components. Unless those other components are of exceptionally bad engineering, they will convey the source faithfully, at least as far as human perception is concerned. The loudspeaker is the weak link. If a system sounds bad, and the reason isn’t that it was incorrectly setup by the user, then chances are that the loudspeaker is flawed or is inappropriate for that particular system. ‘Sound Reproduction’ goes into great depth about how loudspeaker behavior affects the end sound, and what loudspeaker attributes are desirable and what is substandard performance.

A loudspeaker is only part of the equation for sound quality, and the other major component that affects the resultant sound is the room. The room acoustics will have a profound effect on the sound, in some cases for the better and other cases for the worse, especially at low frequencies. Dr. Toole explains in detail how the loudspeakers can behave in the acoustic situations of both normal and treated rooms, and how human hearing perception responds to room acoustics. Humans can hear the rooms, and we can also hear through the rooms, that is to say, we can quickly adapt to room acoustics and hear the sound signature of the source of acoustic emission beyond the room acoustics. A room will shape the sound of the loudspeaker in it, but we can still hear how well the loudspeaker is performing after our hearing has acclimated to the acoustics, which usually occurs very quickly. However, some acoustic environments will take a greater toll on the emitted sound than others, and Dr. Toole elucidates some of the actions that can be done to cope with suboptimal room conditions.

For more information see: Early Reflections and Small Room Acoustics

The Circle of Confusion YouTube Video Discussion

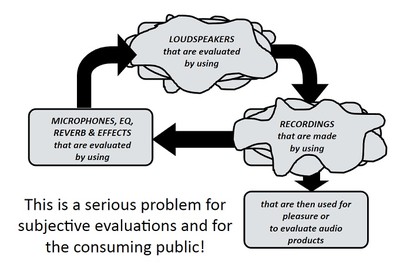

The Circle of Confusion

One subject brought up throughout the book is what Dr. Toole calls the ‘circle of confusion.’ The circle of confusion is, very simply stated, that there can be no standard of sound reproduction since there is no standard of production from the recording and sound engineering end. What is the point of achieving a near-perfect audio system when the content that it reproduces can vary so wildly due to the fact that there was no consistent reference point by which they were reproduced? One startling fact that Dr. Toole discusses is how badly flawed many of the monitoring systems are that were used in recording and mastering studios. If the audio systems that were used to mix and master the recordings had a poor frequency response, the sound engineers will be creating a sound mix that sounds good on that particular system, but when that sound mix is reproduced on a system that is far more accurate and linear, it can sound odd, since it was created with inherent compensations for an acceptable sound on a problematic sound system to begin with. Imagine trying to build a house when your square tool doesn’t have any true 90 degree angles, your level finder doesn’t quite match truly level surfaces, and the inch readings on your ruler are a bit too short versus standard inch length.

An example of how the circle of confusion can cause problems is if the sound system that the recording was created with was very lean on bass, the sound engineer, who may be ignorant of this audio system’s shortcoming, will mix the recording to sound 'even' down to bass frequencies, but when played back on a system that has a normal bass response, that recording can then sound bloated with excessive bass. Dr. Toole also discusses a related problem to this circle of confusion; sound engineers who have hearing loss from years of mastering music at loud playback volumes will unwittingly mix music that sounds ‘even’ to them, but the measures they take to compensate for their poor hearing exaggerates those areas in the frequency response to those who have normal hearing. Hearing loss will most commonly occur as a reduction in high-frequency sensitivity, so sound engineers can end up boosting high-frequencies to compensate for their hearing, and that can leave the sound mix to be blazing hot in treble for those of us with good hearing.

This brings me to another point that Dr. Toole mentions in the book that isn’t quite related to sound quality, but I was a bit shocked to find out: the OSHA noise exposure guidelines were not set to prevent hearing loss but only to preserve enough hearing that conversational speech at a 1 meter distance at the end of a working life is possible. OSHA noise exposure criteria actually allows for a substantial amount of hearing damage to occur. It turns out that the only thing that mattered in safeguarding worker’s hearing was employee productivity and not their quality of life at all. Just when I think I am becoming too cynical, I find out I am not cynical enough!

Something else that Dr. Toole explains that might be a bit provocative is the ineffectiveness of automated room correction equalization such as Audyssey outside of bass frequencies. He makes a very good case to this effect, and I am forced to agree with him. Automated room correction routines are more of a band-aid for flawed loudspeakers rather than an improvement for typical room acoustics. The solution isn’t an equalization system that is blind to the conditions that it measures or the object it is measuring; the solution is acquiring speakers that don’t need any assistance from equalization in the first place. Automated room correction can actually make things worse by attempting to correct for diffraction and acoustical interference effects which change with distance and angle, so in adjusting the frequency response for one position it can mess up the response for many other positions. Its true usefulness is mostly only in bass frequencies, and even then it can only really help a single listening position unless multi-sub solutions have been involved to reduce seat-to-seat variations.

For more info, see: Bass Optimization for Home Theater with Multi-Sub

Another subject that Dr. Toole covers at length is the shortcomings of stereo sound compared to multi-channel formats. Stereo sound recordings can sound great, as so many of us know, but has some severe disadvantages versus 5.1 (or more) surround sound mixes. In a typical surround sound mix, in addition to a soundstage with a stable center image regardless of listening position that the center speaker provides, the surround speakers can create a greater sense of a different acoustic environment than the room that they are situated in. The psychoacoustic research that Dr. Toole discusses which explains the superior effects of multi-channel sound with respect to stereo and even quadraphonic sound is a fascinating read. However, much of the music industry and many audio reproduction equipment manufacturers continue to adhere to two-channel sound despite its psychoacoustic inferiority.

The Case for Reading Sound Reproduction

These are just a few of the subjects covered in ‘Sound Reproduction.’ Any issue related to the discussion of what audio systems can sound good and why they sound good are covered including: what makes a loudspeaker good, where to place it so it sounds best, how to calibrate the system for the most optimal effect, how to treat the room to achieve the best acoustics for the system, what content is most revealing of a system’s strengths or weaknesses, and much more. Dr. Toole doesn’t just dwell on home audio, he also discusses commercial cinema audio, recording control rooms, concert venues, and even touches on headphone audio. ‘Sound Reproduction’ has nearly 470 pages of content filled with the scientific understanding of what makes for excellent sound reproduction. It can get somewhat technical at points, but the author does a great job at making complex matters accessible and clear to a general readership. The book was written to make it readable in pieces based on the subject the reader is interested in, so some points that the author makes are revisited on multiple occasions. However, even those who read it from cover to cover will benefit from this slight repetition, since the book is dense with material, and a subject or point that is explained from multiple angles can be better understood by a non-specialist reader when that subject material is a bit complex. An accompanying website is under construction. It will contain additional information and simplified guidance about how to apply the scientific findings in real life listening room and home theater projects.

Those of us who are knee-deep in the audio hobby can spend a great deal of time discussing and debating aspect of sound reproduction, but many of these subjects of discussion and debate are long-settled issues of scientific research. For those of us who still take empirical data seriously (seems like it is fewer people than it used to be nowadays), taking the time to read through ‘Sound Reproduction’ would cut through a lot of the nonsense that floods the audio scene, whether based on irrelevant personal anecdotes or hyperbolic marketing claims. So, despite its length and dense content, reading ‘Sound Reproduction’ will end up being a major time-saver for audio hobbyists. Furthermore, Dr. Toole makes the complicated subjects of acoustics and psychoacoustics intelligible and interesting through his engaging writing style, no doubt honed over many decades of trying to explain these concepts to non-scientists. This book is not a chore to read like some kind of arcane research paper. It is easily-digestible and a pleasure to read, and it is made all the more accessible by moments of personal recollection, history, and humor. ‘Sound Reproduction’ is a worthwhile investment of time for the audio hobbyist and a badly-needed dose of reality to the audio industry.