Do Our Expectations Determine Our Experience of Sound More Than We Realize?

The audio hobby is filled with practices and products that are touted to improve the sound of your system but are known by experts to do nothing significant to alter the sound. Examples are numerous and have been well-covered by Audioholics in the past, such as exotic cables, harmonizing crystals, and extravagant “high-fidelity” equipment racks, yet it is common to see rave customer reviews of these patently absurd ideas. How is it that so many audio enthusiasts swear by differences in equipment or recording when we know that the changes made are either non-existant or well below audible thresholds? We know that these effects are not acoustic but rather psychological, so the question becomes: how does the mind pull this trick?

State of Mind

The first thing that should be understood is that in many cases the actual listening experience is altered by the state of mind of the listener. If the expectation of an immediate experience is different, the experience itself can be different, so it is not as if the listener perceives the same sound but merely changes their mind about the quality of that sound. Human experience does not have direct access to the input of any of our senses. Sensory input is not reported to our conscious mind directly, and our brain acts as a filtration system. The many filters of our brain are necessary in order for us to navigate the world, or else we would be overwhelmed with an excess of irrelevant information. One of these filters is the use of expectations of our environment to shape our experience. This is a streamlining of experience that is done to save our attention for things that matter, such as things that are out of the norm, or expected things that are critically important. We aren’t just perceiving what our senses relay; our perceptions are modified by what we anticipate what will happen.

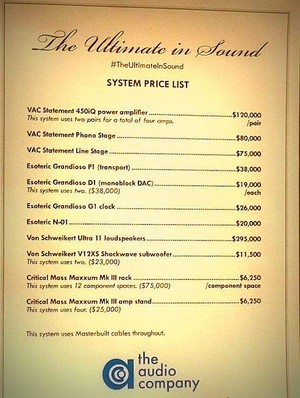

A system as expensive as this surely sounds flawless?

This expectation filter is a ‘top-down’ effect that can affect our experience during the sensory stimulus and also after the experience[1]. By ‘top-down,’ we mean that expectation is a complex and high-level idea that can affect the lower-level ‘nuts and bolts’ functioning of the brain rather than something that forms from a mass of simpler parts to reach higher cognition. The effect of expectation on perception is especially strong when the sensory input is weak, noisy, or ambiguous. The bias of expectation can not only change qualitative aspects of how well something is perceived but what is actually being perceived (maybe this is why ghost sightings, UFO sightings, and other reported paranormal experiences seem to occur mostly in vague circumstances for the senses, i.e., in dark places)[1]. People rely most heavily on prior knowledge and ideas when sensory input is ill-defined or ambiguous, and an example of that is when you move around a living space that you know well even in almost total darkness[1]. One experience that can be quite ambiguous is trying to listen for changes in sound from small tweaks or upgrades in a sound system, especially when aural memory has been shown to degrade after three to four seconds. That would seem to be a prime opportunity for expectations to be heavily manifest in perception.

‘Schema Theory’ provides one top-down explanation of how high-level ideas about the world create a bias in how we perceive the world[2]. We need a way to quickly select and process useful information, so we need selection criteria that sorts out relevant data from the torrent of input coming in from our senses. An idea or hypothesis about how the world works can provide selection criteria by telling the perceiver what to look for and how to interpret incoming information. This mental model of how the world works- this “schemata”- gives focus and structure to what information will be used and how it will be used. According to Schema Theory, information that matches prior expectations will be more easily stored and recalled than information that does not. Scheme Theory neatly explains why some people are so stubborn to change their ideas even in the face of contradicting evidence. Their minds are not geared to receive and or memorize anything that does not fit their preconceptions. Not only do expectations change the experience during the stimulus, but they also affect what is stored in memory from the experience[3].

Why Do Audiophiles Fall for Placebo Effect - YouTube Discussion

The Placebo Effect

The Placebo Effect

One of the most powerful ways that expectations can influence perception is the well-known “placebo effect”. The placebo effect is a psychological phenomenon where a result of a treatment could not have been due to the treatment itself but rather the patient’s belief in the treatment. Placebos can take various forms and are generally just a vehicle for convincing the patient of the effectiveness of some otherwise-ineffective treatment[4]. The placebo effect is a testament to the power of the mind and is backed by a large body of scientific research. A couple of placebo studies that are relevant to our subject of sound reproduction was conducted in the field of hearing aid research and found that the placebo effect needed to be accounted for in hearing aid trials[5][6]. In one study, a hearing aid touted to be more advanced and improved over a regular hearing aid was reported to have better sound quality by 75% of the participants over a standard hearing aid, even though their performance was identical[6]. Participants believed that they could hear better with the supposedly superior hearing aid, and testing did show slight but statistically significant improvements in speech-in-noise recognition testing. The pertinence of this research to high-fidelity audio could not be more clear.

A converse effect of the nocebo effect is the placebo effect, which has been shown to be a powerful effect as well[7]. The nocebo effect is when negative effects come from a treatment simply that stems from the belief that an adverse reaction will occur. The nocebo effect is so powerful it can even render an otherwise-effective treatment to be ineffective. We could easily imagine scenarios in audio reproduction where a nocebo effect can change someone’s experience of the sound, such as measurably high-performance equipment that might look dull or strange that which dominates blind listening tests but loses sighted listening tests. Negative expectations of particular equipment designs can color the experience for the worse.

Placebo and nocebo researchers have to carefully run their trials in a double-blind manner or to put it another way, they are careful to avoid knowing which of their test subjects received the inert placebo/nocebo treatment and who receives active treatment. They deliberately avoid this knowledge due to another powerful factor that can also play a role in our subjective experience of audio reproduction called ‘confirmation bias.’ Confirmation bias is a tendency to ‘search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that affirms one’s prior beliefs or hypotheses’. When we think something is supposed to happen or did happen, we are more prone to looking for evidence that it did happen rather than anything that points to the contrary. Scheme theory provides a clear explanation for the way that confirmation bias operates since, of course, ‘prior beliefs or hypotheses’ are just the ‘schemata’ that we look for so as to keep a stable model of the world. Our own memories are victims of confirmation bias, and we more easily recall information that can support our beliefs rather than information which can debunk them[3]. In the audio hobby, we can see confirmation bias in action in people who swear by certain designs, practices, and technologies and will disregard flaws in favor of anything that could validate their preconceptions, no matter how trivial the information. Outside of actual listening experience, as a loudspeaker reviewer, I frequently see confirmation bias in the form of comments from readers who latch onto imperfections in measurements of a loudspeaker as evidence of a design’s inferiority, even if they do not seem to understand the practical impacts of these ostensible flaws.

Sight Over Sound?

Our aural experience is especially susceptible to the influences of expectation when vision is also involved in the overall experience, which is so often the case. As a sense, the mind gives sight “an unparalleled, asymmetric power over other senses,” because it is our primary sense. Research estimates that eighty to eighty-five percent of perception, learning, and cognition are mediated through vision[8]. One well-known phenomenon that illustrates vision’s dominance over sound is the “McGurk Effect” where watching someone speak can change the perception of certain parts of speech from what they actually said. Another example is the “ventriloquist effect” where a sound is misperceived as emanating from a spatial location that can be seen to have similar motion when it actually emanates from a different invisible source. Experiments have shown that people can be conditioned to hear sound from a misaligned spatial source using the ventriloquist effect, and this conditioning can last even after no visible sound cue is present[9]. In other words, we can use vision to distort our auditory sense of localization, and this skewed localization can linger even if there is no longer any visual stimuli until it is reset by correct visual cues. When vision is involved with hearing, our visual sense will always be given the driver’s seat.

Contrary to popularly held belief, vision’s dominance over hearing is especially true in the realm of music  even though we tend to think of music as a purely auditory experience. This surprising fact has been demonstrated over multiple experiments, and one of the most striking of those experiments concerns groups of people who guessed winners from music competitions[10][11]. In this experiment, the performance of the top three finalists from ten prestigious international classical music competitions was replayed to both expert musicians and novices, and these participants were asked to guess who the winner was based on what they had seen or heard. Of the experts and novices, these two types were further divided into two groups: those who only heard the performance and those who only saw the performance. Among both experts and novices, those who only saw the performance were far better able to determine the winner than those who heard the performance who actually fared no better than chance. What is even more surprising is that another group of participants who were shown both audio and video also fared no better than chance in guessing the competition winner. These results show that the sight of the performance plays the major role in our appreciation of the musical performance, and, to quote the study’s conclusion, “the findings demonstrate that people actually depend primarily on visual information when making judgments about music performance[11].”

even though we tend to think of music as a purely auditory experience. This surprising fact has been demonstrated over multiple experiments, and one of the most striking of those experiments concerns groups of people who guessed winners from music competitions[10][11]. In this experiment, the performance of the top three finalists from ten prestigious international classical music competitions was replayed to both expert musicians and novices, and these participants were asked to guess who the winner was based on what they had seen or heard. Of the experts and novices, these two types were further divided into two groups: those who only heard the performance and those who only saw the performance. Among both experts and novices, those who only saw the performance were far better able to determine the winner than those who heard the performance who actually fared no better than chance. What is even more surprising is that another group of participants who were shown both audio and video also fared no better than chance in guessing the competition winner. These results show that the sight of the performance plays the major role in our appreciation of the musical performance, and, to quote the study’s conclusion, “the findings demonstrate that people actually depend primarily on visual information when making judgments about music performance[11].”

High-end turntable (left) and CD player (right). How can such ostentatious-looking components sound anything less than aural perfection?

While there are differences between watching a player perform music and seeing equipment reproduce music, the relevance of that experiment to high-fidelity audio should still be clear. It would be easy to assume that something that looks higher-end must offer better performance, especially to laypeople. And, as has been seen in many deeply flawed equipment measurements, higher-end gear can easily be more concerned with appearance than sound reproduction. With the expectation of better performance, the brain can easily slant perception towards that end, and so glitzy but bad performing equipment can be perceived to have good sound regardless of its actual audio characteristics. And the inverse could also easily occur, where plain-looking equipment could be perceived to be dull sounding even if the audio performance is near-perfect.

It looks like a million bucks, so it must sound like a million bucks...

One Man's Meat, Another Man's Poison?

All of this brings us to the question: if our experience of an audio system is good, regardless of its actual audio performance, is that such a problem? What does performance matter when our perception of sound is so thoroughly ruled and twisted by our biases and expectations? One major problem here is that the forces that shape our expectations and thus our perception can change so drastically from individual to individual that our experiences with audio will never be consistent. This inconsistency is magnified when accurate sound reproduction is disregarded. When audio equipment strives for accuracy, the sound should provide some level of consistency across different systems. While our perception of sound will always be skewed in some manner, a balanced, neutral sound should bring some consistency, especially for those who do not bring as many expectations to a listening experience and so will not be affected as much by these biases. One person’s perfect sound can be another person’s unlistenable cacophony, but that may be alleviated somewhat if more manufacturers aimed for objective neutrality as an audio performance goal.

Is Audiophile Snobbery & Snake Oil Ruining Audio? - YouTube Discussion

A reliance on expectations alone for a good sound also creates space for bad actors in the audio industry, the type of equipment manufacturers that Audioholics has long battled against. There are vendors who traffic in fraud by selling over-priced nonsense and dressing it up with absurd technical babble to fool layman. Those who do not know better will install these ineffective gimmicks into their system and may well perceive an improvement in the sound, but it will only have been due to a placebo effect. The problem here, much like ‘snake-oil’ vendors of yore who sold bogus cure-all medicines, is that this rewards charlatans and con-men, and that gives the struggling hi-fi audio business an element of crookedness that it could really do without. High-fidelity audio may be in better shape if neophytes weren’t afraid of getting swindled, but, for the uninitiated, there is no telling where valid engineering ends and hucksterism begins.

Objective Measurements To the Rescue or Detriment?

The only way to ensure that audio equipment is accurately reproducing sound is to measure them using objective, standardized testing. Contrary to so much of the audio press industry, simply listening to audio equipment is nowhere near good enough to determine its accuracy, no matter who is doing the listening. The problem is that few people have the time, resources, or expertise to measure their equipment, so they have to rely on third-party testers for verification of audio accuracy. This can be a double-edged sword, because looking at measurements does create a whole new set of expectations that can influence the listening experience. That can be a problem when the people looking at the measurements don’t know how to correctly interpret what they are seeing, but that can be alleviated somewhat by commentary on the meaning of the measurements by testers, providing the testers themselves understands the significance of the measurements. And this all assumes that the measuring was done correctly; sometimes problems can occur during measuring, and sometimes the people doing the measuring simply are not using proper testing methods. However, while providing measurements is not without its own set of problems, it still provides a useful service overall for those seeking accurate audio equipment.

The only way to ensure that audio equipment is accurately reproducing sound is to measure them using objective, standardized testing. Contrary to so much of the audio press industry, simply listening to audio equipment is nowhere near good enough to determine its accuracy, no matter who is doing the listening. The problem is that few people have the time, resources, or expertise to measure their equipment, so they have to rely on third-party testers for verification of audio accuracy. This can be a double-edged sword, because looking at measurements does create a whole new set of expectations that can influence the listening experience. That can be a problem when the people looking at the measurements don’t know how to correctly interpret what they are seeing, but that can be alleviated somewhat by commentary on the meaning of the measurements by testers, providing the testers themselves understands the significance of the measurements. And this all assumes that the measuring was done correctly; sometimes problems can occur during measuring, and sometimes the people doing the measuring simply are not using proper testing methods. However, while providing measurements is not without its own set of problems, it still provides a useful service overall for those seeking accurate audio equipment.

As a loudspeaker review, I have to be especial ly aware of the powerful force that expectation can have on perception in order to give fair evaluations. I am no less vulnerable to these forces than anyone else, and neither is any other audio equipment reviewer. No one is immune to the influence of their expectations, so be wary of reviewers who claim impartiality. In fact, a landmark 2012 psychological study found that those who have more sophisticated cognitive abilities may be even more susceptible against these biases and blind spots than the average person[12]. “Experts” are more in need of objective data to stay grounded than anyone. Everyone should be mindful that we do carry biases and expectations everywhere we go, and we should be willing to accept change when enough evidence contradicts our views. However, if you see someone enjoying a system that you know to be less than perfect, it may be a good idea to simply let them enjoy their system rather than attempt to impart your knowledge of their system’s deficiencies. If they believe their system to be outstanding and enjoy the sound it produces, there is no sense in potentially ruining a good thing. An audio hobbyist who is one-hundred percent satisfied with their own system is a rare bird indeed.

ly aware of the powerful force that expectation can have on perception in order to give fair evaluations. I am no less vulnerable to these forces than anyone else, and neither is any other audio equipment reviewer. No one is immune to the influence of their expectations, so be wary of reviewers who claim impartiality. In fact, a landmark 2012 psychological study found that those who have more sophisticated cognitive abilities may be even more susceptible against these biases and blind spots than the average person[12]. “Experts” are more in need of objective data to stay grounded than anyone. Everyone should be mindful that we do carry biases and expectations everywhere we go, and we should be willing to accept change when enough evidence contradicts our views. However, if you see someone enjoying a system that you know to be less than perfect, it may be a good idea to simply let them enjoy their system rather than attempt to impart your knowledge of their system’s deficiencies. If they believe their system to be outstanding and enjoy the sound it produces, there is no sense in potentially ruining a good thing. An audio hobbyist who is one-hundred percent satisfied with their own system is a rare bird indeed.

References:

- de Lange, Floris P., Micha Heilbron, and Peter Kok. "How do expectations shape perception?." Trends in cognitive sciences 22, no. 9 (2018): 764-779. (PDF)

- Wikipedia contributors, "Schema (psychology)," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Schema_(psychology)&oldid=925260703 (accessed November 28, 2019).

- Taylor, S. E., & Crocker, J. (1981). Schematic bases of social information processing. In E. T. Higgins, C. A. Herman, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Social cognition: The Ontario Symposium on Personality and Social Psychology (pp. 89-134). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. (PDF)

- Schwarz, Katharina A., Roland Pfister, and Christian Büchel. "Rethinking explicit expectations: connecting placebos, social cognition, and contextual perception." Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20, no. 6 (2016): 469-480. (PDF)

- Dawes, Piers, Samantha Powell, and Kevin J. Munro. "The placebo effect and the influence of participant expectation on hearing aid trials." Ear and hearing 32, no. 6 (2011): 767-774.

- Dawes, Piers, Rachel Hopkins, and Kevin J. Munro. "Placebo effects in hearing-aid trials are reliable." International journal of audiology 52, no. 7 (2013): 472-477.

- Wikipedia contributors, "Nocebo," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Nocebo&oldid=924529979 (accessed November 28, 2019).

- Politzer, Thomas. “Vision is Our Dominant Sense.” Brainline. https://www.brainline.org/article/vision-our-dominant-sense (accessed November 28, 2019).

- Berger, Christopher C., and H. Henrik Ehrsson. "Mental imagery induces cross-modal sensory plasticity and changes future auditory perception." Psychological science 29, no. 6 (2018): 926-935. (PDF)

- Palusis, Kelly Lynn. "Expression and Emotion in Music: How Expression and Emotion Affect the Audience’s Perception of a Performance." (2017). (PDF)

- Tsay, Chia-Jung. "Sight over sound in the judgment of music performance." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 36 (2013): 14580-14585. (HTML)

- West, Richard F., Russell J. Meserve, and Keith E. Stanovich. "Cognitive sophistication does not attenuate the bias blind spot." Journal of personality and social psychology 103, no. 3 (2012): 506. (PDF)

Further Reading:

Witten, Ilana B., and Eric I. Knudsen. "Why seeing is believing: merging auditory and visual worlds." Neuron 48, no. 3 (2005): 489-496. (PDF)

Vanderbilt, Tom. “The Colors We Eat.” Nautilus. http://nautil.us/issue/26/color/the-colors-we-eat (accessed November 28, 2019).

Thompson, William Forde, Phil Graham, and Frank A. Russo. "Seeing music performance: Visual influences on perception and experience." Semiotica 2005, no. 156 (2005): 203-227. (PDF)

Lehrer, Jonah. “Why Smart People are Stupid.” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/tech/frontal-cortex/why-smart-people-are-stupid (accessed December 1, 2019).