A Primer on Trademarks

Intellectual property is a matter that regularly plays into the lives of audiophiles. The most prevalent example is, of course, the copyrights in the music we enjoy. However, the ever-litigious Monster Cable reminds us of another area of intellectual property – trademarks.

Trademarks, copyrights and patents are frequently confused for one another, as are the rights that each is designed to protect. Trademarks are a particularly challenging because the tests of infringement are largely subjective; kind of like Justice Potter Stewart’s analysis on obscenity: I know it when I see it. However, understanding the fundamentals of trademark will help prevent potential problems with famous mark owners as well as help smaller shops defend their own rights.

What are trademarks and why are they used?

At the most basic level, trademarks are used to identify a source of goods or services. Unlike copyrights, which protect an expression (songs, poems, paintings, etc.), and patents, which protect an invention (the turntable, the CD player, the microphone), trademarks serve as a way to tell the world where a particular good or service came from. Trademarks cannot be generic or descriptive (BOTTLED WATER for bottled water, for instance), while fanciful or arbitrary marks like GOOGLE or YAHOO! are the strongest.

Let’s say a guy named Klipsch makes some speakers. He put a lot of time and energy into

developing and designing his speakers, and he’s now ready to sell them to the

public. His first priority is to find a

way to let people know which speakers on the store shelves are his, so he calls

them Klipsch (he’s not very creative).

Let’s say a guy named Klipsch makes some speakers. He put a lot of time and energy into

developing and designing his speakers, and he’s now ready to sell them to the

public. His first priority is to find a

way to let people know which speakers on the store shelves are his, so he calls

them Klipsch (he’s not very creative).

Over time, Klipsch builds a reputation for making really nice speakers and people start asking for them by name. At this point, Klipsch has developed what is called “goodwill.” The public has come to associate the Klipsch brand with a certain quality and can expect the speakers to perform a certain way.

Thus, on the offensive side of the equation, companies use trademarks to identify their goods and services. As those goods and services develop goodwill in the public, trademark owners can use their marks defensively to protect those rights.

The Lanham Act, which governs federal trademarks, gives the owner of a trademark a monopoly on the use of that mark in certain circumstances. Going back to the example above, no one other than Klipsch will be allowed to sell speakers with the name Klipsch. If this were not the case then people who wanted to buy speakers made by Klipsch would not know which ones came from the man himself until it was too late. If consumers cannot look at the label and know where the product came from then there might as well be no label at all.

Registration

Trademarks can be registered on a state level or federal

level (as well as internationally).

While trademark owners do not have to register their marks to protect

their rights, registration provides certain benefits. For instance, registering a mark federally

tells the world that a claim is being made to that mark and serves as evidence

of use, which makes it easier for that person to defend against any allegations

of infringement. It also provides more

options to the owner if he or she is ever required to file an infringement

lawsuit against someone else.

Additionally, federal registration allows the owner to prevent

potentially conflicting marks from becoming registered in the first place, which

is much cheaper and easier (and less damaging) than bringing an infringement

claim later.

Trademarks can be registered on a state level or federal

level (as well as internationally).

While trademark owners do not have to register their marks to protect

their rights, registration provides certain benefits. For instance, registering a mark federally

tells the world that a claim is being made to that mark and serves as evidence

of use, which makes it easier for that person to defend against any allegations

of infringement. It also provides more

options to the owner if he or she is ever required to file an infringement

lawsuit against someone else.

Additionally, federal registration allows the owner to prevent

potentially conflicting marks from becoming registered in the first place, which

is much cheaper and easier (and less damaging) than bringing an infringement

claim later.

The so-called “circle R” is used to tell the world that the mark has been federally registered. If a mark has been registered then it is imperative that the “circle R” be used with the mark, as a failure to do so will preclude the owner from recovering certain damages. On the other hand, if a mark is not registered then the “circle R” should not be used. Instead, the “TM” (for trademark) or “SM” (service mark) should appear with the mark, which tells the world that a common law claim is made.

Trademark infringement and the scope of trademark protection

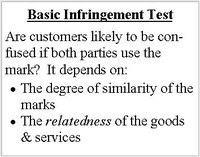

Trademark infringement comes in a variety of fashions. However, the main question to be answered in

every case is the same: Are consumers likely to be confused if both parties use

the mark?

Trademark infringement comes in a variety of fashions. However, the main question to be answered in

every case is the same: Are consumers likely to be confused if both parties use

the mark?

The most blatant examples of trademark infringement are the fake Rolexes sold on the streets of New York, or the fake Gucci purses auctioned on eBay. Someone makes a copy of a famous product and attaches the famous trademark to it. This is called “passing off.” On the other hand, someone might take the product of another, remove the label and stick their own mark on it. This is called “reverse passing off.”

The most common types of trademark infringement, however, are not so obvious and oftentimes are done unintentionally. This is when the question of likely confusion gets broken down into: (1) How similar are the marks to one another?; and (2) How related are the goods and services?

The answer to each of these questions is a matter of degree, and each depends on the other when answering the ultimate question of whether consumers are likely to be confused. The more similar the marks, the less related the goods and services need to be in order to find a likelihood of confusion. Conversely, if the goods are virtually identical then the marks do not have to be as similar in order to confuse consumers.

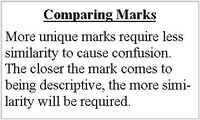

Comparing the Marks

The first step is to look at the marks themselves. There are two primary types of marks:

standard character (also called word marks, which covers just plain words) and

design (a picture or drawing, with or without words). However, other things can also be trademarks,

so long as they serve to identify the source of goods. Sounds, colors and even smells have been

considered trademarks. However, word and

design marks are by far the most common.

The first step is to look at the marks themselves. There are two primary types of marks:

standard character (also called word marks, which covers just plain words) and

design (a picture or drawing, with or without words). However, other things can also be trademarks,

so long as they serve to identify the source of goods. Sounds, colors and even smells have been

considered trademarks. However, word and

design marks are by far the most common.

There are benefits and drawbacks to each type of mark. Word marks protect against others’ use of similar sounding or similar looking words. When comparing word marks, the only thing that is important are the words themselves. For example, by protecting the word mark COCA COLA, the soda maker can prevent anyone from calling their soda drink by a similar name. POCA ROLA would be prohibited, regardless of how the words were printed. On the other hand, without design mark protection, another soda maker could print the name SUPER DRINK on a red label in the same distinctive script as Coke and there probably would be no recourse.

Design marks, however, give broader protection where, as in

the Coke example, the appearance of the mark itself is important. While Coke may not be able to prevent someone

from using the name SUPER DRINK, it probably could prevent someone from printing

that name on a red label in Coke’s distinctive type font.

Likewise, Apple’s trademark for the word APPLE may prevent anyone from calling their computers SNAPPLE or even ORANGE (since they are both fruit), but not from using Apple’s signature drawing of an apple with a bite taken out. Apple’s design mark for the logo would prevent others from using any drawing that looks similar, regardless of the name used.

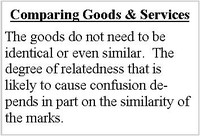

Comparing the Goods and Services

While comparing the marks is relatively straightforward,

analyzing the goods and services is surprisingly challenging. This is mainly because the question centers

not on whether the goods are identical, but whether they are related.

While comparing the marks is relatively straightforward,

analyzing the goods and services is surprisingly challenging. This is mainly because the question centers

not on whether the goods are identical, but whether they are related.

On one end of the spectrum are two companies who both make amplifiers. These products are clearly related. Other examples of clearly related goods might be car stereo head units and home stereo receivers, or receivers and amps. On the other end of the spectrum are two companies where one makes pencils and the other makes jet engines, which are clearly not related.

Somewhere in the middle are two other companies, one making magnets for speakers and the other making tone arms for turntables. If the two were using similar marks, the one claiming infringement might point out that they are both audio products and manufacturers often offer a variety of such products. Therefore, they are related. The company on the other side might point out that speaker magnets are generally sold to speaker manufacturers while tone arms are sold to consumers, and thus are not related. However, remember that relatedness is a matter of degree, so both sides are right.

In such a case, the decision will likely turn on the similarity of the marks. For instance, if both parties are using an identical mark, there is a strong possibility that infringement will be found. However, if one party is using the mark KODIAK and the other is using ZODIAC, infringement is far less likely. While the two have similar appearances and sound very similar when spoken, they have significantly different meanings. The differences between the parties’ marks could be enough to offset the relatedness in their goods.

Conclusion

Trademarks are a complicated yet necessary consideration for any business, and in an industry as competitive and diverse as the audio market, the consequences of not addressing trademark issues early can be devastating. Knowing your market and competitors is a necessary first step, and understanding how trademarks work, the types of trademarks, and the fundamentals of infringement are all important elements in that process.

As a final caution, anyone contemplating filing their own trademark application should consider that doing so improperly can do infinitely more harm than good. An experienced trademark attorney can avoid common pitfalls, advise on potential risks and help strengthen the mark and broaden the scope of protection.

Special thanks to T. D. Ruth of Lassiter Tidwell Davis Keller & Hogan, PLLC for this insightful article.