Mobile Fidelity’s Digital Vinyl Debacle: Are your records really analog?

In September of last year, audio reviewer and analog evangelist Michael Fremer reviewed Mobile Fidelity’s reissue of Truth, the 1968 debut studio album from Jeff Beck. In his review, Fremer praises the sound, saying, “Mo-Fi knocks it out of the park.” The title of this enthusiastic review? “Mobile Fidelity Tells The Truth.” But as Mr. Fremer now knows, that’s not strictly true.

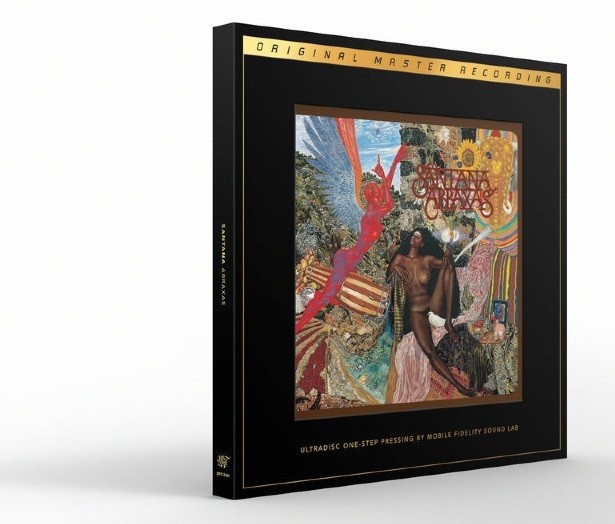

In what has become one of the most widely-publicized scandals in recent memory — for audiophiles, anyway — the record-buying public has recently learned that Mobile Fidelity’s reportedly all-analog vinyl production process actually involves converting the master tape source material into digital DSD files before remastering and pressing records. It is undeniable that this digital step helps to preserve the precious master tapes by reducing the wear-and-tear associated with running the tapes multiple times, as would otherwise be required. But Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab, the California-based record label specializing in audiophile-approved reissues of beloved albums from artists like Santana, Marvin Gaye, and Thelonious Monk, has other reasons for its use of DSD.

Simply put, the company has said that the DSD transfer step is necessary in order to achieve the best-sounding results, and that it is completely transparent to the master tape. This notion is anathema to analog devotees who prize the natural sound that they associate with a purely analog production chain. MoFi records are expensive, up to $100 each, but customers are willing to pay more for records that are labeled AAA — meaning they were recorded, mixed, and mastered in the analog domain.

Many vinyl enthusiasts believe that digital recording and playback reduce musical enjoyment, and so the purity of an all-analog process means something to them. So does the attendant exclusivity; the nature of a purely analog production chain inherently limits the number of copies that can be produced (more on this topic later). As a result, MoFi records have traditionally been released as limited editions.

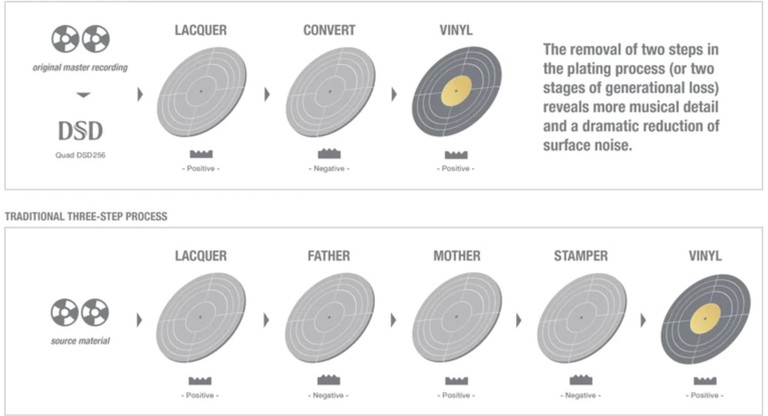

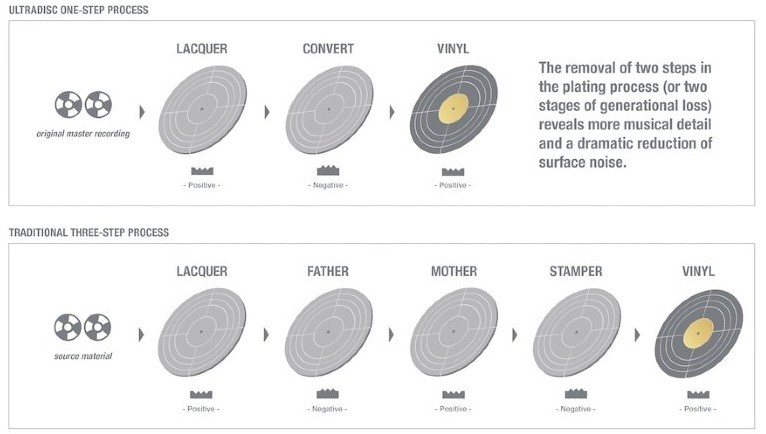

We now know that MoFi began this now-controversial use of digital technology in 2011. Before that, MoFi really was a purely analog outfit. Founded by mastering engineer Brad Miller in 1977, the company had many years of success before succumbing to the vinyl slump of the 1990s. Mobile Fidelity declared bankruptcy in 1999. But just two years later, Jim Davis, owner of the Chicago-based retailer Music Direct, acquired Mobile Fidelity and its proprietary mastering chain. Together, Davis and MoFi have surfed the wave of vinyl resurgence that continues to swell two decades into the 21st century. (According to Wikipedia, sales of vinyl albums grew almost 500% between 2007 and 2013; 2021 sales figures marked a 30-year high.) Mobile Fidelity was back on top, with its limited-edition audiophile releases selling out regularly. One key to this success was a marketing strategy aimed directly at traditional audiophiles who treasure the old-school way of doing things. You’d be unlikely to miss the words “Original Master Recording” emblazoned across the jacket of a MoFi record. The most prized products of the label are known as “One-Steps,” so called because they cut out intermediary steps common to normal vinyl production. The result, they say, is a sound that is closer to that of the original master tape. Inside each One-Step is a piece of marketing material explaining in great detail how the records are made. It states that “Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab engineers begin with the original master tapes and meticulously cut a set of lacquers.”

The ins and outs of vinyl production may be considered common knowledge among a certain subset of audiophiles, but if you’re in need of a refresher, let’s turn to a very helpful excerpt from Michael Fremer’s 2016 review of one of Mobile Fidelity’s most lauded releases: Santana's Abraxas.

Records are made by first cutting grooves in a lacquer, which is an aluminum disc coated with a soft paint-like compound. The cut lacquer is quickly metal-plated. Prying the metal from the lacquer produces a ridged metal part that can be used to press records. That is how Mobile Fidelity is doing it, and why it’s called a ‘one-step’ process. The advantage of course is that you’re one generation from the tape. The disadvantage is that once the stamper wears out after around a thousand records, you have to cut another lacquer. In the real world of record manufacturing, the metal part (called ‘the father’) is again plated, resulting in a playable grooved disc commonly referred to as ‘the mother.’ The ‘mother’ can be plated to produce a second generation stamper that’s used to press records. The ‘mother’ can then be reused many times to produce well more than one hundred stampers, each of which is capable of pressing many (hundreds or thousands of) records. The fewer times you rely on the same mother to produce stampers, and (the) fewer records you press with each stamper, the better the records generally will sound.

BREAKING NEWS: ALL Mobile Fidelity titles since 2015 Are digital?

The explainer materials included with MoFi’s One-Steps illustrate the benefits of avoiding the sonically deleterious “father/mother” steps, and outline the company’s streamlined process. There is no mention of DSD, nor of digitization of any kind. How is it, then, that the secret is out? According to Fremer, unsubstantiated rumors of MoFi’s duplicity had been circulating for months when Mike Esposito, owner of Phoenix’s The ‘In’ Groove record store, took them public on July 14th via his YouTube channel. He claimed that unnamed “reliable sources” had dished the dirt about Mobile Fidelity’s use of digital files in its production process. The video soon made its way to John Wood, Mobile Fidelity’s Executive Vice President of Product Development. Without consulting MoFi owner Jim Davis, Wood contacted Esposito and invited him to the company’s Sebastopol, California headquarters to set the record straight. One week after his first video went public, Esposito published a second video, in which he interviews MoFi’s engineers, and they confirm Mobile Fidelity’s use of DSD. This admission led to a deluge of outrage from the community of analog-loving audiophiles, who felt justifiably that they had been purposefully misled. For years, MoFi had maintained that its process was pure analog. “It’s the biggest debacle I’ve ever seen in the vinyl realm,” said Kevin Gray, a mastering engineer with over 2,500 entries on the crowdsourced audio database Discogs, including acclaimed LP reissues from Craft Recordings, Intervention Records, Resonance Records, Rhino Records, Speaker's Corner, and others. “We finally got the information out that it was from digital,” said Fremer, “and in all honesty, Mobile Fidelity has a black eye over this.” Mobile Fidelity suddenly found itself in crisis-management mode — something the small firm was definitely not prepared for.

Mobile Fidelity - Interview on Mastering With Shawn Britton, Krieg Wunderlich & Rob LoVerde

Syd Schwartz, the company’s Chief Marketing Officer, had this to say:

Mobile Fidelity makes great records, the best-sounding records that you can buy. There had been choices made over the years and choices in marketing that have led to confusion and anger and a lot of questions, and there were narratives that had been propagating for a while that were untrue or false or myths. We were wrong not to have addressed this sooner.

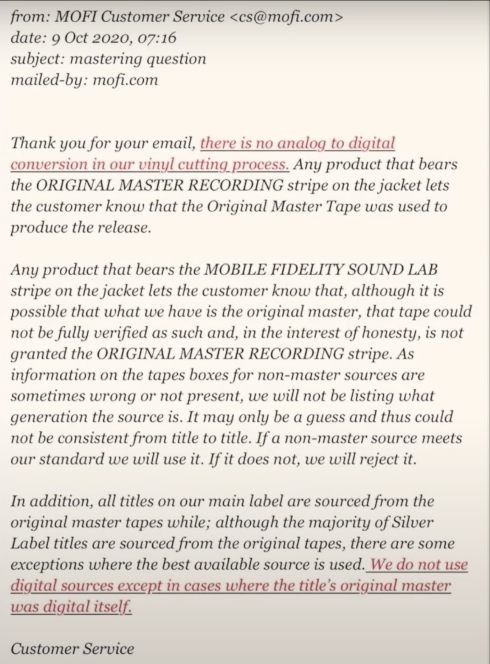

Needless to say, this half-hearted non-apology wasn’t sufficient. It also didn't acknowledge the fact that MoFi didn’t merely fail to mention its use of digitization — the company flat-out lied about it. In one of his several YouTube videos on the subject, Fremer displays an email from Mobile Fidelity customer service sent to a MoFi customer on October 9th, 2020. This customer had reportedly reached out asking for clarification about MoFi’s mastering process.

The response from Mobile Fidelity states:

Thank you for your email, there is no analog to digital conversion in our vinyl cutting process. Any product that bears the ORIGINAL MASTER RECORDING stripe on the jacket lets the customer know that the Original Master Tape was used to produce the release. … All titles on our main label are sourced from the original master tapes… We do not use digital sources except in cases where the title’s original master was digital itself.

“As in Watergate, the cover-up is always worse than the crime.”

— Michael Fremer

While Esposito has not revealed who tipped him off about the scandal, we do know that the cracks in Mobile Fidelity’s all-analog facade started to show earlier this year when the label announced that Michael Jackson’s Thriller would be released as a One-Step remaster. The announcement indicated that the source for the reissue was, of course, the original master tape. But unlike MoFi’s other One Step releases, most of which were limited to between 3,500 and 7,500 copies, Thriller would see a run of 40,000. Immediately, questions began to arise. Because of the mechanics of the One-Step process and the limited production potential from each lacquer, a run of 40,000 copies would require MoFi to play back the master tape at least 40 times. Realistically, the number would be higher than that. Sony Music Entertainment, which owns and closely guards the masters, would never allow it. Michael Ludwigs of the YouTube channel 45 RPM Audiophile wondered in one of his videos how MoFi’s claims could possibly be accurate. Fremer conjectured that either MoFi had made an analog copy of the original master tape (which the company could run as many times as necessary), or that perhaps a digital transfer was being used. Fremer says that he reached out to MoFi, and was told that the Thriller records would be made from a copy — on analog tape — of the original master. But he says that his contact at MoFi asked him not to announce that fact, as the label was planning its own press release after The High End international audio show, which took place in Munich in May of 2022. Fremer says that when the online press release first came out, it mentioned the involvement of mastering engineer Bernie Grundman (who worked on the original recordings of Thriller). Later, according to Fremer, Grundman’s name vanished. At no point did the press release mention the use of a copy of the master tape, rather than the original. Nor did it say anything about the use of digitization. Those paying attention knew something had to be amiss.

Not that you can’t make good records with digital, but it just isn’t as natural as when you use the original tape.

— Bernie Grundman

As we have established, the cat eventually worked its way out of the bag, and now Mobile Fidelity’s use of DSD is public knowledge. But that’s not the end of the story, because this revelation raises another underlying question that has turned some parts of the audiophile world upside-down.

Is Analog Really Better?

There

are, of course, many audiophiles who have long argued that digital audio delivers

higher resolution, along with a superior signal-to-noise ratio, allowing for

higher dynamic range. But many diehard analog purists are suddenly faced with

the possibility that everything they believed about the analog-digital divide

might be wrong. I mentioned earlier that people buy MoFI records because they

champion a “pure analog” philosophy, and because there is a natural appeal to

owning a limited-edition collector’s item. But there’s another huge reason why

people like MoFi records: the sound.

There

are, of course, many audiophiles who have long argued that digital audio delivers

higher resolution, along with a superior signal-to-noise ratio, allowing for

higher dynamic range. But many diehard analog purists are suddenly faced with

the possibility that everything they believed about the analog-digital divide

might be wrong. I mentioned earlier that people buy MoFI records because they

champion a “pure analog” philosophy, and because there is a natural appeal to

owning a limited-edition collector’s item. But there’s another huge reason why

people like MoFi records: the sound.

People are also buying the records because they sound f***ing amazing. And generally, they are some of the best versions of these albums ever made, sound-wise. …This reveal, that a DSD stage has been used in the production process of these MoFi releases, doesn’t take away from the fact that these records still sound great.

John Darko of darko.audio

If MoFi records are celebrated by analog devotees, and they are made from a digital copy of the original recording, doesn’t that prove that the digitization process really is completely transparent? Yes and no. In one of his YouTube videos, Fremer points out that “every analog-to-digital converter in the world sounds different from one another. And every studio has their own preferences because they all sound different.” I don’t have much experience with analog-to-digital converters, but I do know that different DACs sound different, and that has to go both ways. So yes, the analog-to-digital conversion might be adding some kind of coloration to the sound as it was originally captured. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the use of digitization has been detrimental to the sound. In Fremer’s 2013 review of Mobile Fidelity’s The Band reissue, he says, “Listening to Mobile Fidelity's reissue you’ll have no doubt you’re listening to a tape source — and not because you can hear tape hiss.”

And consider this excerpt from his 2016 review of Mobile Fidelity's One Step reissue of Santana's Abraxas album from 1970:

Halfway through this One Step's side one, I said to myself, ‘This might be the best record I've ever heard.’ I meant by that the technical quality of the record and how much it resembles tape in four critical parameters: the wide dynamics and low bass response, the unlimited dynamic range, the tape-like sense of flow, and especially the enormity of the soundstage presentation.

Mobile Fidelity has confirmed that Abraxas was made with a digital DSD transfer.

In 2015, Fremer reviewed a trio of mid-period Miles Davis quintet albums reissued by MoFi — Sorcerer (1967), Nefertiti (1968), and Filles de Kilimanjaro (1969). Here’s what he had to say about their sound quality, as compared to the all-analog original versions:

There was an unpleasant dryness and starkness to the sound of (the) originals, accompanied by unpleasant grain. That is why it is easy to write that these three reissues from Mobile Fidelity sound far superior to the originals. They are far more transparent, detailed, and texturally more supple, as well as being harmonically more fully fleshed out. Like other reissue labels, Mobile Fidelity has its hits and misses. These three double 45rpm releases, along with much of the Miles catalog, are among Mobile Fidelity’s best work to date.

Caught Red Handed???

I

think it’s clear from these reviews that Mobile Fidelity’s process, however

blasphemous it may seem to analog fundamentalists, is sonically successful.

MoFi just as easily could have made analog tape copies of the original masters,

but the company’s engineers say that their chosen method of using DSD produced

better results. There’s no way for us to know for sure, but there’s also no

reason to doubt that claim. Personally, I don’t believe that MoFi’s engineering

team acted maliciously, but there’s no doubt that, at the marketing level (and

presumably the executive level), the company promoted a convenient lie for

years, and in doing so, has lost the trust of its customer base. No, these

records don’t suddenly sound different, but there are other factors to

consider. The records will almost certainly lose considerable value on the used

market, screwing over collectors in the process. (If you’ve ever searched for a

MoFi record, you’ll know that there are people who buy them, never open them,

and then sell them later for many multiples of their original price.) And the

company’s response to the scandal was neither as clear nor as swift as it

should have been. Recently, though, MoFi began updating the sourcing

information on its website, and redesigned its explainer materials to include

the DSD transfer step. The company also agreed to its first formal interview,

resulting in a broadly-circulated article from the The Washington Post.

According to the Post’s Geoff Edgers, MoFi began using DSD on a 2011 reissue of

Tony Bennett’s I Left My Heart in San Francisco. By the end of that

year, DSD was being used in 60 percent of the company’s vinyl releases. With

the exception of one album from jazz pianist Bill Evans, all of MoFi’s One Step

records have been made with the DSD transfer step.

I

think it’s clear from these reviews that Mobile Fidelity’s process, however

blasphemous it may seem to analog fundamentalists, is sonically successful.

MoFi just as easily could have made analog tape copies of the original masters,

but the company’s engineers say that their chosen method of using DSD produced

better results. There’s no way for us to know for sure, but there’s also no

reason to doubt that claim. Personally, I don’t believe that MoFi’s engineering

team acted maliciously, but there’s no doubt that, at the marketing level (and

presumably the executive level), the company promoted a convenient lie for

years, and in doing so, has lost the trust of its customer base. No, these

records don’t suddenly sound different, but there are other factors to

consider. The records will almost certainly lose considerable value on the used

market, screwing over collectors in the process. (If you’ve ever searched for a

MoFi record, you’ll know that there are people who buy them, never open them,

and then sell them later for many multiples of their original price.) And the

company’s response to the scandal was neither as clear nor as swift as it

should have been. Recently, though, MoFi began updating the sourcing

information on its website, and redesigned its explainer materials to include

the DSD transfer step. The company also agreed to its first formal interview,

resulting in a broadly-circulated article from the The Washington Post.

According to the Post’s Geoff Edgers, MoFi began using DSD on a 2011 reissue of

Tony Bennett’s I Left My Heart in San Francisco. By the end of that

year, DSD was being used in 60 percent of the company’s vinyl releases. With

the exception of one album from jazz pianist Bill Evans, all of MoFi’s One Step

records have been made with the DSD transfer step.

Michael Fremer was not happy with the Washington Post story, which he described as “clickbait,” saying in a video that the intention of the piece was to humiliate analog fans:

That’s the writer’s intention. His intention is to make all of us look like fools, who don’t like to listen to records cut from digital when there’s a tape (that could have been used instead). And 90% of the time I can hear it, and I’ve said it. And in all the negative reviews I’ve given to Mobile Fidelity records — which are many, I’ve given many negative reviews to Mobile Fidelity records — …I never suspected they were cut from digital. I heard something I didn’t like; I thought it was maybe only EQ-related. But I never suspected it was because it was cut from a digital source. …I took their word for it. I trusted them.

— Michael Fremer

Indeed, Fremer has written negative reviews about several MoFi releases, as recently as February of 2022, when he made it clear that the One Step release of Carole King’s Tapestry album sounded notably worse than the original version. (Interestingly, Fremer revealed his opinions ONLY after he captured a digital selection of each version and asked readers to choose which one they thought sounded better. The readers didn’t know which was which. Of the 719 readers who responded, only 37% preferred the MoFi One Step.) In any case, Fremer’s objections to the Washington Post piece went beyond his suspicions that Edgers intended the article as a “gotcha” for analog-lovers. The article states that Fremer rebutted Esposito’s initial claim about MoFi’s use of digital. According to Edgers, Fremer said that he had his own source, and that Esposito was wrong. Fremer denies this vehemently. Instead, he says that he merely stated that it was wrong of Esposito to report unsubstantiated (at the time) rumors, and that doing so was not responsible journalism. Then again, Fremer has also pointed out (snidely, some might say) that Esposito is not a journalist. Fremer did say that a journalist, such as himself or one of several colleagues he could suggest, should have been invited to Sebastopol instead of Esposito.

Perhaps MoFi owner Jim Davis took note of Fremer’s comments because he later agreed to an interview with The Absolute Sound’s Jonathan Valin and Robert Harley. Valin reviews high-end loudspeakers and turntables for the magazine, for which Harley serves as Editor-in-Chief. (Incidentally, Harley is now Michael Fremer’s boss; in June of 2022, Fremer left his longtime post at Stereophile — and its sister website, Analog Planet — to rejoin The Absolute Sound, where he worked many years ago. He will soon be launching an associated website called Tracking Angle, which already has its own YouTube channel.) Below are what I believe to be the two most important questions and answers from Davis’s interview with The Absolute Sound:

TAS:

Why did you decide to master from DSD files rather than from analog master tapes, as you used to do? What are the advantages of mastering from files vis-a-vis mastering from tape, and what (if any) are the limitations?

Jim Davis:

Some record label tape vaults changed policy regarding shipment of master tapes. At that point our only option for those recordings was to go to the master tapes. Once we were able to access these masters, the dilemma was how can we best retrieve the information from the master? We experimented with making analog copies from the master. Various tape stocks (½”, 1”) and speeds (15 ips, 30 ips) were tried but rejected. There was no way to overcome the noise-floor disadvantages of copying from one analog tape to another. When we tried DSD, it was immediately clear this was a vastly superior method for maximizing information retrieval. Developed as an archival format, DSD is sonically transparent, with a very low noise floor. Combined with the painstaking transfer process… the capture is a virtual snapshot of the master, revealing detail and nuance at a level that conventional methods could not. Counterintuitively, this capture yields, in our evaluation, superior sonics compared to a cut that is direct from the analog tape to the lathe. The process of achieving these captures at a remote studio location is expensive and time-consuming. We ship our proprietary gear, including our Tim de Paravicini-modified Studer A80 tape machine, to the studio, rent studio time, and fly and lodge our engineer for several weeks at a time. The process of making a DSD capture using our techniques takes a day or more alone for each tape. These are long and exhausting days, and I’m proud of the hard work MoFi engineers put into each project, and of the results they consistently achieve. I’m not aware of any other audiophile record label that puts that time and expense into each release. Beyond the additional time, effort, and expense, I’m not aware of any sonic limitations of using this process.

TAS:

The revelation that MoFi cuts from digital masters has suggested to many that the advantages of a purely analog chain are imaginary. How do you reply to that line of thinking?

Jim Davis:

That’s a debate that has and may continue to go on for years. I can only speak for our process. We did extensive evaluations of all aspects of the mastering process and found that using our proprietary gear with these steps yields the best sonic results. In the end it’s up to each individual listener to make his or her own decision as to what sounds best. We feel the excellent reviews from so many of our customers and the press support our point of view. For that, we are grateful.

While I think that most people will agree that Mobile Fidelity has committed a serious misstep, there are (and will continue to be, I’m sure) varying opinions about the big-picture implications that this revelation might have for the greater analog-versus-digital debate. Some will surely say that this whole fiasco finally proves that digitization can now be totally transparent to an analog source, and so digital audio must be considered superior because of its many technical advantages over analog. Others will surely cling to their beliefs, bolstered by the fact that the MoFi releases in question were still recorded, mixed, and (mostly) mastered in the analog domain, and that no edits were performed in the digital realm. The fact that a DSD transfer was used to produce MoFi’s excellent-sounding records won’t be enough to make analog-centric professionals embrace the “Pro Tools” way of doing things. Mobile Fidelity will undoubtedly be more concerned with finding a way to smooth out the dents in its blemished reputation and redeem itself in the eyes of its customers. There is a notion that audiophiles are “all about the sound,” above all things. This MoFi situation will put that idea to the ultimate test. If people love the sound of MoFi records, will they continue to buy them? Will analog lovers continue to pay top-dollar for vinyl that’s been stained by the sin of digitization? I expect that there will be some former MoFi customers who simply draw a line in the sand. This kind of willful deceit is so upsetting that they’ll never buy MoFi again, no matter how good the records sound.

Ultimately, you could say, it doesn’t matter. It only matters how it sounds. But that’s really not so. Everybody that buys these records is entitled to know what they’re buying.

--Michael Fremer

The problem is (that) ‘analog’ has become a hype word, and most people don’t know how records are made. And you can very factually say ‘this record was sourced from the original analog master tape,’ and you’re not lying. But that doesn’t disclose to the consumer what’s going on between the beginning of it and the final product.

— Mike Esposito

What's at Stake

Wrapping

up, I have to wonder what effect this situation might have on Music Direct, the

parent company of Mobile Fidelity. In a typical year, Mobile Fidelity’s record

sales account for nearly 20% of the retailer’s revenues. Will disgruntled

vinyl-buyers now look elsewhere for their online purchases of music and/or

audio equipment? And then there’s MoFi electronics, the hardware leg of the

company, which produces well-respected turntables and phono stages. Sometime soon,

MoFi electronics will be releasing a highly-anticipated line of

loudspeakers — a first for the company —

from the celebrated designer Andrew Jones, known for his high-value speakers

from Elac and Pioneer, and expensive high-performance designs from TAD. Many

audiophiles in the market for new speakers (myself included) have been waiting

for over a year to see what Jones’s next creation will be, with most

speculating that the new speakers will be more expensive than Elacs but more

affordable than TADs. Will the launch of these new speakers be dragged down

into the muck? On the one hand, Andrew Jones clearly had nothing to do with

Mobile Fidelity’s wrongdoing. On the other hand, it is conceivable that the

MoFi name has been so badly tarnished that people simply won’t want a product

associated with the brand and marked with its logo. Then there’s MoFi

Distribution, which handles the import and U.S. sales of a number of popular

audio brands, including Wharfedale, Quad, and newcomer HiFi Rose. Will these companies

try to distance themselves or maybe even jump ship? What, if anything, can

Mobile Fidelity’s higher-ups do to manage this crisis of faith?

Wrapping

up, I have to wonder what effect this situation might have on Music Direct, the

parent company of Mobile Fidelity. In a typical year, Mobile Fidelity’s record

sales account for nearly 20% of the retailer’s revenues. Will disgruntled

vinyl-buyers now look elsewhere for their online purchases of music and/or

audio equipment? And then there’s MoFi electronics, the hardware leg of the

company, which produces well-respected turntables and phono stages. Sometime soon,

MoFi electronics will be releasing a highly-anticipated line of

loudspeakers — a first for the company —

from the celebrated designer Andrew Jones, known for his high-value speakers

from Elac and Pioneer, and expensive high-performance designs from TAD. Many

audiophiles in the market for new speakers (myself included) have been waiting

for over a year to see what Jones’s next creation will be, with most

speculating that the new speakers will be more expensive than Elacs but more

affordable than TADs. Will the launch of these new speakers be dragged down

into the muck? On the one hand, Andrew Jones clearly had nothing to do with

Mobile Fidelity’s wrongdoing. On the other hand, it is conceivable that the

MoFi name has been so badly tarnished that people simply won’t want a product

associated with the brand and marked with its logo. Then there’s MoFi

Distribution, which handles the import and U.S. sales of a number of popular

audio brands, including Wharfedale, Quad, and newcomer HiFi Rose. Will these companies

try to distance themselves or maybe even jump ship? What, if anything, can

Mobile Fidelity’s higher-ups do to manage this crisis of faith?

Mobile Fidelity’s President, Jim Davis, released an official statement addressing the controversy. I’ll leave you with his words:

We at Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab are aware of customer complaints regarding use of digital technology in our mastering chain. We apologize for using vague language, allowing false narratives to propagate, and for taking for granted the goodwill and trust our customers place in the Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab brand.

We recognize our conduct has resulted in both anger and confusion in the marketplace. Moving forward, we are adopting a policy of 100% transparency regarding the provenance of our audio products. We are immediately working on updating our websites, future printed materials, and packaging — as well as providing our sales and customer service representatives with these details. We will also provide clear, specific definitions when it comes to Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab marketing branding such as Original Master Recording (OMR) and UltraDisc One-Step (UD1S). We will backfill source information on previous releases so Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab customers can feel as confident in owning their products as we are in making them. We thank you for your past support and hope you allow us to continue to provide you the best-sounding records possible — an aim we've achieved and continue to pursue with pride.

--Mobile Fidelity’s President, Jim Davis

MoFi Class Action Lawsuit

MoFi has been hit with a class action lawsuit potentially worth millions of dollars. The lawsuit says that MoFi has been “using digital mastering or digital files — specifically Direct Stream Digital (‘DSD’) technology — in its production chain” for over a decade, and that during this time, the company continued to “misrepresent to consumers that it did not use digital mastering, or otherwise failed to disclose the use of digital mastering, while still charging the same price premium for the Records as if they were entirely analog recordings.” The complaint goes on to say that, “Had (the) Defendant not misrepresented that the Records were purely analog recordings, or otherwise disclosed that the Records included digital mastering in their production chain, (the) Plaintiff and putative Class Members would not have purchased the records, or would have paid less for the records than they did."