Dolby Atmos Best Speaker Setup Practices In the Home

It’s not surprising that Dolby Atmos can be a confusing topic, even for enthusiasts who pride themselves on being the “go-to guy” for home theater tips and explanations when friends and family are looking to upgrade their entertainment experiences. There’s just a lot of technical information to absorb, and countless variables that can confound even the best laid plans. The purpose of this article is to provide a general understanding of how Atmos works, and to clarify the best speaker practices to follow when setting up an Atmos home theater. We discuss the minimum number of speakers you need in your home theater to get a proper Dolby Atmos experience.

To help guide us on our way, Audioholics founder Gene DellaSala recently hosted a livestream with John Traunwieser, a recording and mixing engineer for film and television, whose credits include work on multiple Star Wars movies, the Hunger Games franchise, and other big titles. John offered unique insights from the perspective of a professional whose job it is to record and mix orchestras at Fox Studios, Warner Brothers, and Sony Pictures in Los Angeles, as well as at Air Studios and Abbey Road in London. John has worked with many notable composers, including James Newton Howard, John Williams, John Powell, Hans Zimmer, Henry Jackman, and John Debney. He also works as a mix tech at the Fox Studios dubbing stages, assisting several Oscar-winning mixers. His hands-on experience working in the Dolby Atmos format helped us to bridge the sometimes sizable gap between the intent of the artists and professionals who create our entertainment content, and us — the folks at home who want to enjoy that content in a way that satisfies our individual needs while simultaneously respecting the effort and care that went into crafting it. Let’s get started with some background information on what Dolby Atmos is, and how it works.

Need Help with Home Theater Design & Speaker Layout - Check out our approved channel partner Dreamedia AV for Consultation

Need Help with Home Theater Design & Speaker Layout - Check out our approved channel partner Dreamedia AV for Consultation

Dolby Atmos Primer

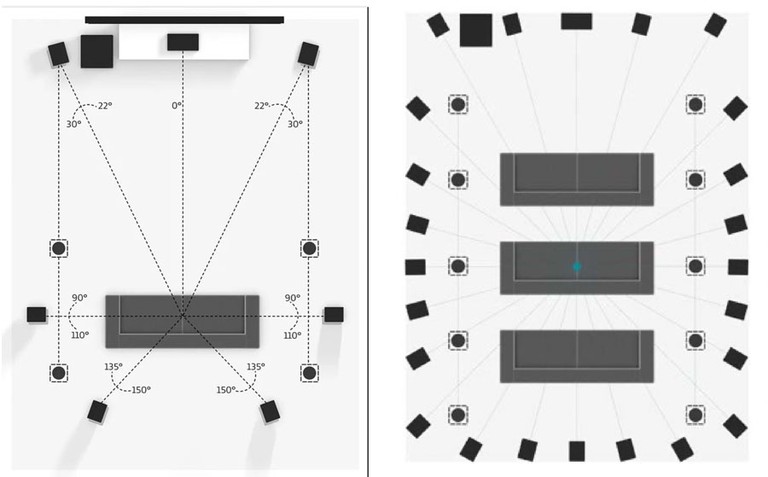

Dolby Atmos is an immersive surround sound format that expands on previous systems by adding height channels, ideally to be played back by speakers mounted onto or into the ceiling above the listeners. This allows sounds to be interpreted as three-dimensional objects placed anywhere within a three-dimensional sound field. In earlier surround systems, each audio track was assigned to a channel, correlating to a specific speaker. A 5.1-channel system used 5 speakers plus a subwoofer. A 7.1-channel system used 7 speakers plus a subwoofer. Dolby Atmos systems can scale up or down, adding additional speakers as needed depending upon the size of the room. This means the content is not tied to any specific speaker layout or configuration. Mixers creating Dolby Atmos content still have the ability to assign a track to a specific channel, using a 7.1.2 format. This is equivalent to a 7.1 system with one stereo pair of height channels. This 7.1.2 layout is referred to as the “bed” for Dolby Atmos. But mixers also have the option to assign a track to an audio “object.” Each object is associated with an apparent source location in the theater described by a set of three-dimensional rectangular coordinates relative to the defined audio channel locations and theater boundaries. This allows content creators to precisely place and move sounds almost anywhere, including overhead, to create an immersive listening experience. During playback, the Dolby Atmos system renders the audio objects in real time based on the known locations of the loudspeakers present in the theater. This way, the audio object is heard as originating from its designated set of coordinates. The technology can adapt automatically to take advantage of the number and placement of the speakers, whether there are five ear-level speakers and four overhead, or 24 ear-level speakers and ten overhead. For home theater, the gold standard layout is 7.1.4, with seven ear-level speakers, and four overhead.

Dolby Atmos Speaker Layouts - 7.1.4 for home (left pic) ; Cinema Layout (right pic)

This object-based system has a number of benefits over conventional multichannel technology, in which each source track is assigned to one of a fixed number of channels (5.1 or 7.1, for example) during post production. First of all, systems like that did not scale up or down. If you were listening to a 7.1-channel soundtrack on a 5.1-channel system, any information being sent to the two rear surround channels simply wouldn’t be played back on your system. Secondly, conventional multichannel systems required the mixer to make assumptions about the playback environment, which often didn’t align with the speaker layout and physical setup of the theater. Object-based technology allows the mixer more creative freedom and more confidence that, in a properly set-up Atmos system, the listener will hear the content as it was meant to be heard. From a mixing perspective, Dolby Atmos delivers higher spatial resolution, along with the addition of the height plane, giving the mixer a significantly larger, three dimensional “audio canvas” on which to build the soundscape. This space can be used for exaggerated effects flying around overhead, but it can just as effectively be used to add subtle spaciousness, or to increase clarity by moving certain sounds off-screen, or by widening the music to create an open sonic space for dialogue.

The following is an excerpt from an explainer from Dolby’s gaming division, going into slightly more depth about object-based audio. It describes “static” objects, which are assigned to specific bed-layer speaker locations, and “dynamic” objects, which can be placed and moved freely around the three-dimensional theater soundscape. These concepts apply to home theater as well as to gaming.

The foundation of Dolby Atmos is based on two types of audio objects: static and dynamic. Static objects are commonly referred to as “bed objects,” as they are defined as non-moving objects that are mapped to specific speaker locations. Typically, this is a 7.1.2 layout and is referred to simply as “the bed,” which corresponds to traditional non-Atmos configurations like 7.1 and 5.1. Dynamic objects are audio objects that can freely move around the entirety of the listening field. The bed is essential because it provides a format that is still applicable for audio that works best in a channel-based environment. Diffuse elements such as ambience, reverb, or anything else that doesn't need to dynamically move around the room would be panned to the bed. Additionally, content that was used in a dynamic object can be folded down into the bed when needed, based on prioritization and object management. Dynamic objects are used for precise positioning and/or free movement of content within the listening space. One of the most immediate features of Dolby Atmos is the ability to represent sound on the Z axis. … This doesn’t just allow for a height plane, it actually unlocks the ability for sound to be reproduced in its full three-dimensional glory. One can take some first steps and place sounds in zones along the listener’s perimeter, such as front, side, back, and above. This is appropriate for most content and can create extremely immersive and compelling experiences. The next steps would be to approach design from a layered approach and include concepts such as depth, frequency, proximity, perspective into creation of individual assets as well as the scene as a whole.

— Dolby Gaming

Dolby Atmos Content

What does all of this translate to in real-world listening? A lot of that depends not only on the system used to play back the content, but also on the content itself. Not all Dolby Atmos content is created equal. Some titles with “Dolby Atmos” audio use only the bed, with no dynamic objects. In such cases, larger home theaters with additional speakers don’t see much benefit compared to smaller systems with fewer speakers. According to John Traunwieser, objects are generally used for two things, and two things only:

-

Atmospheric sounds that you want to fill the space, filling in the gaps with extra speakers.

-

Point source sounds. These are sounds effects: things whizzing by, or particular effects that you want to localize better.

If the mix consists entirely of the 7.1.2 bed, but you have a bigger system with more speakers — 9.1.6, for example — the Dolby Atmos renderer can fill in those speakers, but you won’t hear any unique information in the additional speakers if you don’t have object content in the mix. Here’s a concrete example. Let’s say you have a large, multi-row theater. Where a typical 7.1.4 layout would have just one side surround speaker on each side wall (to the left and right of the listening position), a large theater might have 5 side surround speakers on each side wall, so that multiple rows of seating are covered. Now imagine a scene in a movie in which a monkey swings down from a tree in front of you, whooshes right past you, and then lands high up in a tree behind you. The specificity of the sound in this scene would depend on how it was mixed. If the mixer used only the bed and no dynamic objects, you would notice a few things. When the monkey whooshed by you, the sound would pass through all 5 of the side speakers simultaneously, so there would be less localization and a less realistic sense of movement. If the mixer used a dynamic object for the monkey, the sound would pass through each of the 5 side speakers individually. The algorithm is scaled in the renderer, depending on the layout. The second difference you’d notice would relate to the overhead sounds. The Atmos bed only has one stereo pair of height channels (that’s the “.2” at the end of 7.1.2). So if the mixer used only the bed, the sounds coming from up in the treetops would have left-to-right separation, but no front-to-back separation. You would simply hear the monkey move from above, down to ear level, and then back above. If the mixer used a dynamic object for the monkey, you would hear it go down from the treetop in front of you, past you at ear level, and then up into the treetop behind you.

There is a lot of static Atmos out there, especially in TV/streaming releases. This is usually if the shows were mixed primarily in 5.1 or 7.1, and then up-mixed to Atmos. TV and streaming mixes usually have 1/10th of the time as a theatrical mix, so not enough time is spent on objects.

— John Traunwieser

There are a few reasons why an Atmos mix might have limited use of objects. John Traunwieser says that, when it comes to a film’s music, a lot of soundtracks “aren’t really mixed in Atmos because you don’t want instruments flying around the room. If you just stick with the bed, (even) if it’s an ‘Atmos’ mix, you would only be hearing music through the bed. Sometimes, he says, a mixer might utilize objects for certain strategic things, such as placing a choir in the ceiling speakers to get it “off the screen,” or to push certain sounds wider off the screen so that they’re not in the way of the dialogue. But in many cases, mixers shy away from using objects because a soundtrack rich with object information doesn’t always translate down (to channel-based formats) in a way that is desirable. Many theaters — both professional cinemas and home theaters — still aren’t equipped for Atmos at all. Atmos titles therefore need to be delivered to the studio in a channel-based format, such as 7.1, in addition to the Atmos mix. And there often isn’t enough time or money available to create two totally separate mixes. In fact, budgetary limitations are one of the main reasons why some Atmos titles consist primarily of “bed” material. Creating individual objects for dozens of tracks and carefully placing them and moving them around takes a lot of time, and time is often in short supply.

You would think that something like Star Wars, or any high-budget Marvel show, or whatever, you’d think that the budget is out the window and you try to get the best result that you want, (but) there are so many factors at play. I don’t want to tread on any toes, but it’s a collaborative effort, and so you will do the best that you can in any environment, but sometimes you have many different opinions from many different people. And a lot of films that I work on, they do these test screenings to random people, and then you’re having a whole other set of feedback from random people watching unfinished content. And depending on the scores of those screenings, they will go back, re-cut the film, re-edit something, re-record the music, do all kinds of stuff. The best product that comes out is when the vision is clear, and it’s executed well, and everybody respects each other in their expertise. And you get the best result that way. … There’s always a budget and a time constraint. Unfortunately, audio is always the end of the process, so the film is finished, and the audio mix is always the last thing. And for some reason, we operate like high-schoolers in that everything gets delayed and delayed and delayed, and pushed to the last minute. And then everybody tries to cram and get everything done to make the release date.

— John Traunwieser, on the Atmos mix for The Last Jedi

Dolby Atmos Theatrical Mix vs Near-Field Mix

Many

Dolby Atmos movies actually get two mixes; the theatrical mix that is played in

the movie theaters, and the near-field mix for home entertainment. Any

big-budget movie that will be released in theaters will first get a theatrical

mix; most of the time and budget are devoted to this mix. If budget allows, a

second near-field Atmos mix for home entertainment is then created. This mix is

typically done in a much shorter period of time, though the mixers have the

benefit of a completed theatrical mix to use for reference. Finally, a 5.1/7.1 mix might be made, often in just a day or

two. Time and budget are the key factors here, but another is the intended use

of the movie or TV show. If the title is being made for Netflix, Disney+, or

HBO Max, it stands to reason that the near-field mix will get the most time and

attention. Sometimes a studio will request a theatrical mix for a streaming

title, either for archival purposes, or just in case the title ever gets a

theatrical release. For some Atmos mixes, the Dolby renderer can do an

automated down-mix to 5.1/7.1, and the results are acceptable. As discussed

earlier, this is more likely when there is less use of objects. In other cases,

creating a 5.1/7.1 mix from an Atmos mix requires more hands-on tweaking. According

to John Traunwieser,

mixers don’t always have the luxury of time to listen critically to every

format and make the necessary adjustments.

Many

Dolby Atmos movies actually get two mixes; the theatrical mix that is played in

the movie theaters, and the near-field mix for home entertainment. Any

big-budget movie that will be released in theaters will first get a theatrical

mix; most of the time and budget are devoted to this mix. If budget allows, a

second near-field Atmos mix for home entertainment is then created. This mix is

typically done in a much shorter period of time, though the mixers have the

benefit of a completed theatrical mix to use for reference. Finally, a 5.1/7.1 mix might be made, often in just a day or

two. Time and budget are the key factors here, but another is the intended use

of the movie or TV show. If the title is being made for Netflix, Disney+, or

HBO Max, it stands to reason that the near-field mix will get the most time and

attention. Sometimes a studio will request a theatrical mix for a streaming

title, either for archival purposes, or just in case the title ever gets a

theatrical release. For some Atmos mixes, the Dolby renderer can do an

automated down-mix to 5.1/7.1, and the results are acceptable. As discussed

earlier, this is more likely when there is less use of objects. In other cases,

creating a 5.1/7.1 mix from an Atmos mix requires more hands-on tweaking. According

to John Traunwieser,

mixers don’t always have the luxury of time to listen critically to every

format and make the necessary adjustments.

So, why the two Atmos mixes? Wouldn’t the theatrical mix give home theater enthusiasts the best experience? Why make a separate near-field mix? A lot of it comes down to room size, and the distances between the listeners and the speakers. Dialing in a mix for a sweet spot centered on just a couple of people is different from averaging out a mix for a much bigger room with many more rows. A theatrical mix might not be quite as dialed-in for a single spot, but overall it’s better for more people. And so some of the mixing decisions will change based on the environment in which the mix will be played back. In a large theater, the seats on the left-hand side might be 75 feet away from the speakers on the right side of the theater. And so panning can’t be as exaggerated, or the people on one side of the theater might miss a significant amount of information. In a large theater, the mixer might choose to have dialogue coming out of all three front LCR channels as opposed to just one spot corresponding to the location of the character. In a near-field environment, where the room is smaller, that’s less of an issue and dialogue will almost always come out of the center. These are just a few of the considerations that mixers must keep in mind when creating a theatrical mix versus a near-field mix for home entertainment.

Most people will only listen to Spotify low quality, or … whatever streaming format it is, and make criticisms (without) understanding the technology… not understanding why it sounds bad.

— John Traunwieser

Dolby Atmos Streaming Quality Compromises

Audioholics readers surely know that streaming media can vary in quality depending upon the bitrates and the compression schemes used to transport the digital data from the cloud to whatever device you’re using for playback. For example, if you’re listening on any decent audio system, you will hear the difference between Qobuz (which delivers lossless high-resolution audio) and Spotify, which as of November 2022, has failed to introduce the Hi-Fi tier that it announced in February of 2021. Spotify still uses lossy compression for all streams. Practically all of the other audio streaming services, including Tidal, Apple Music, and Amazon, offer lossless audio. Unfortunately, lossless audio is NOT the norm when it comes to streaming video content. Video streaming services have to accommodate 4K picture in addition to audio, and there’s only so much bandwidth to go around. So while Dolby Atmos audio is offered by many of the leading streaming services (Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime Video, HBO Max), your Apple TV or Roku device isn’t serving up the same lossless audio that you’d get from an Ultra HD Blu-ray disc, or from a high-end server solution like Kaleidescape. That higher-quality Dolby Atmos is packaged within the lossless Dolby TrueHD format first introduced with the original Blu-ray format. Dolby Atmos on streaming services is packaged within the lossy Dolby Digital Plus format, which uses lower data rates. Atmos audio is particularly affected by the use of lossy compression because, according to John Traunwieser, audio objects in Atmos have a different bit rate than the bed channels in streaming media. He says that the bitrate used for objects is “a lot lower than you would think,” and that “if you were to mute the bed channels and only listen to the objects, you wouldn’t be very impressed with what you’re hearing.” That’s another reason why mixers often don’t place critical music information in objects. Dolby Atmos music can sound great, even when streamed on a device like Apple TV. On a Blu-ray, it can be even better. While some audiophiles will remain devoted to two-channel content and gear until the Earth crashes into the sun, others — including Chief Audioholic Gene DellaSala — can’t get enough of Atmos music (aka. Spatial Audio). But if you spend any significant time listening to music in the format, it will become clear that not all of it sounds very good.

Consumer products sometimes outpace professional workflows. It’s like 8K TV. There isn’t any, or hardly any, content in 8K. It’s the same thing with Dolby Atmos. So many music studios still don’t have Atmos (mixing capability) built into them. So what will end up happening is you’ll mix it in whatever format is there, whether it’s stereo stems, 5.1 stems… and then you send it to a mastering person who will up-mix and create an Atmos version based on those stems. Only recently, in the last few years, studios have started to upgrade their rooms and get Atmos setups. So there hasn’t been a ton of content. Obviously the bigger titles have studios that have that capability but there is a lot of stuff out there that has “faux” Atmos, or just up-mixed surround content that wasn’t mixed natively in Atmos. Now you have record engineers that are more savvy to Atmos, who even start recording with more microphones with Atmos in mind.

— John Traunwieser

How

to Set Up a Dolby Atmos Home Theater Speaker System

With great speaker count comes great confusion. Even in the days of 5.1-channel audio, poor speaker positioning was a common cause of bad sound in home theaters. With Atmos, a high-performance home theater will likely have 11 or more speakers and multiple subwoofers, and it’s no wonder that this increased complication causes headaches for those in search of the best performance from their audio systems. Placing the speakers (and seating positions) for a Dolby Atmos theater isn’t hard if you have an ideal room and complete freedom to put everything precisely where it should go. Just fire up a tool like Audio Advice’s interactive home theater designer and you’ll be done before you know it. For most of us, however, it’s not so simple. Realistically, setting up an ideal Dolby Atmos system has its challenges. The purpose of this guide is not to say that your home theater has to be an all-or-nothing, hardcore megabuck system to be worthwhile. Instead, it’s intended to help clear up certain areas of confusion, and to help our readers understand which Dolby Atmos “rules” are the most important to follow, and which ones can be fudged a bit. If you have the ability to build a perfect spec-sheet Dolby Atmos system, do it! If you have to work within the limitations of a multi-use living room, you can still achieve good results if you know what to prioritize. In such situations, a number of questions will probably arise. Do I really need to place speakers on or in the ceiling? How many speakers do I need? How important is it to place the speakers where Dolby recommends?

7.1.4 Speaker Layout is the "Gold Standard" for Home Cinema

As an audio professional, John Traunwieser has some insight into the importance of proper speaker placement. “That’s everything, really,” he said. “When you talk about hearing what the director intended, the artist intended, they are making those decisions in a room that is calibrated, and meeting certain specifications that make it Atmos.” As for the number and configuration of speakers, a 7.1.4 layout is the gold standard that enthusiasts should shoot for whenever possible. That’s not to say that it’s the best configuration for everyone. If your room’s front-to-back length is on the short side, you may only be able to accommodate a 5.1.4 system. If you have a huge theater, you might benefit from a third pair of ceiling speakers, additional “wide” speakers for the front stage, and/or multiple side surround speakers to provide coverage in a multi-row setup. But 7.1.4 is the layout that John most often encounters in the studio, and it’s considered the best layout for a typical home theater.

How Many Speakers for Proper Dolby Atmos Playback Youtube Discussion

Some might be tempted to simplify the installation by using only one pair of overhead speakers, but you need a minimum of four overhead speakers — two in front of the listening position and two behind — in order to recreate the front-to-back movement and three-dimensional localization that object-based audio was designed to provide.

Klipsch Atmos-Enabled (aka. "bouncy house") Speaker

Like Gene, John is not impressed by “bouncy house” reflective-style speakers that sit at ear level and fire upward, with the goal of bouncing sound off of the ceiling to create the aural illusion of height channels. Ditto for Dolby Atmos soundbars. “It’s abusing the (Dolby Atmos) terminology,” John says. “You don’t get the same effect, and I wouldn’t know how to judge a mix listening to content through a system like that.” John’s strong recommendation is to use in-ceiling or on-ceiling speakers, placed as close as possible to Dolby’s official recommendations (with a few minor tweaks that I’ll get to momentarily).

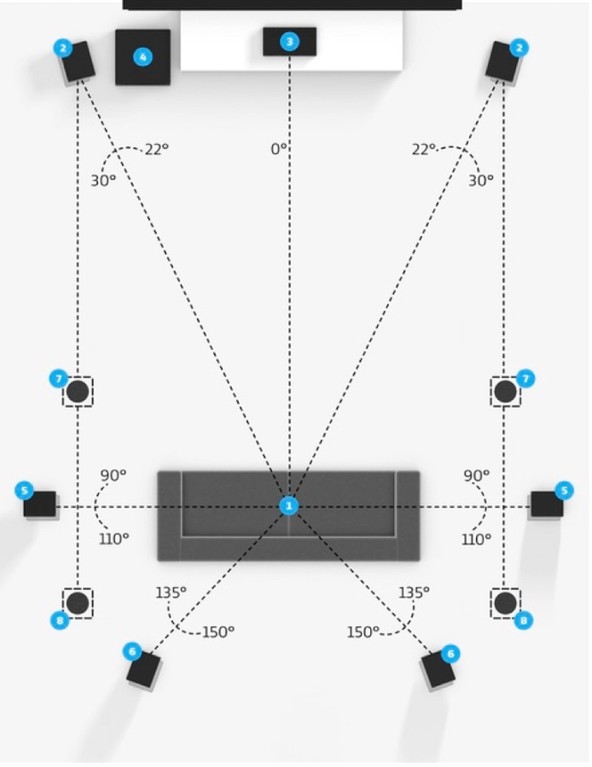

For the sake of brevity, we’ll assume that you know where to place the 7 ear-level speakers in a 7.1-channel system, and we’ll focus on the proper placement of the 4 height channels to complete the 7.1.4 Dolby Atmos configuration. (One thing to note is that Dolby does not recommend the use of dipole speakers for the surround channels in an Atmos setup. These were commonly used in conventional 5.1 and 7.1 setups.) If you do need a refresher on how to set up a 7-channel home theater, the Audioholics website already has you covered. Here’s what Dolby has to say about the use of overhead speakers:

Overhead sound is a vital part of the Dolby Atmos experience. (The best) solution is to install speakers overhead. Most conventional overhead speakers with wide dispersion characteristics will work in a Dolby Atmos home theater. Dolby Atmos audio is mixed using discrete, full-range audio objects that may move around anywhere in three-dimensional space. With this in mind, overhead speakers should complement the frequency response, output, and power-handling capabilities of the listener-level speakers. Choose overhead speakers that are timbre matched as closely as possible to the primary listener-level speakers. Overhead speakers with a wide dispersion pattern are desirable for use in a Dolby Atmos system. This will ensure the closest replication of the cinematic environment, where overhead speakers are placed high above the listeners. If the chosen overhead speakers have a wide dispersion pattern (approximately 45 degrees from the acoustical reference axis over the audio band from 100 Hz to 10 kHz or wider), then speakers may be mounted facing directly downward. For speakers with narrower dispersion patterns, those with aimable or angled elements should be angled toward the primary listening position.

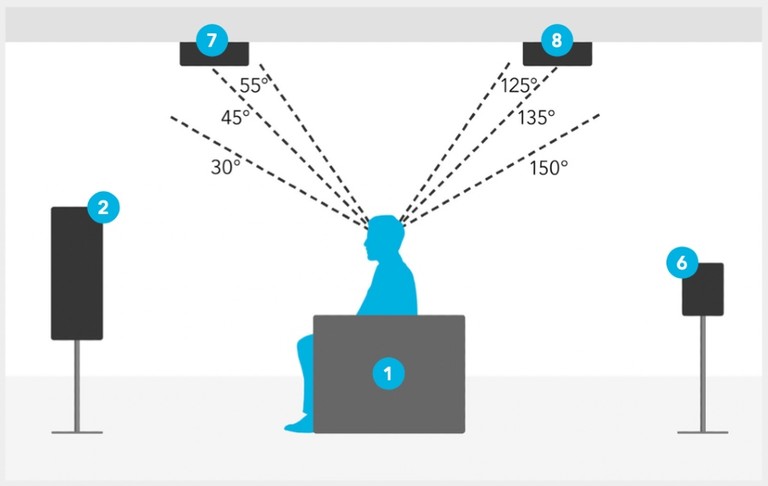

The overhead speakers should be at a height between two and three times the vertical position of the listener-level speakers. The angle of elevation from the listening position (to the front and rear) overhead speakers in a 7.1.4 reference layout should be 45 degrees. This may be adjusted between 30 and 55 degrees if needed. See the related image for the preferred locations of the four overhead speakers as seen from above. The horizontal width should be about the same as the horizontal separation of left and right speakers, placed at ±30 degrees. If this guidance is followed, the overhead side-to-side separation should be 0.5 to 0.7 of the width of the overall layout, depending on the distance to the screen and the front three speakers, relative to the surrounds. It is best to keep the overhead arrangement centered, front to back, over the listening area, even if the front speakers and screen are at a greater distance (from the listener) than the surround speakers.

— Dolby

The advice above from Dolby is specific to home theater Atmos systems; the guidelines for professional cinemas are slightly different. John Traunwieser says that the differences between the Atmos home entertainment spec and the Atmos theatrical spec are interesting, particularly with regard to the placement of height channels. “It’s a little tricky,” he says, “because I’m producing content that could be in a theater or for the home and I have to find a hybrid of both worlds to be able to translate mixes to many different environments.” The differences likely come down to ceiling heights. In a cinema, the high ceilings mean that there is a much greater distance between the listener and the ceiling-mounted speakers, and between the ceiling speakers and the side/rear surrounds.

For home entertainment, (Dolby’s) spec is to widen the heights to have them closer to the (left and right) edges of the room. Whereas for theatrical, the heights are pushed more toward the center of the rooms (again, with regard to left-to-right distance, not front-to-back). And generally, every studio that I’ve been in, the heights are generally closer to the center. Because, you know, it can vary depending on the height of the room, but if your side surround speakers are at ear height or a little higher, if they’re too close to the ceiling speakers, then you don’t get much isolation or separation in the sound, and depending on the treatment in the room and how reflective it is, then it can just blend together and you may as well just have one speaker there, it doesn’t make much of a difference. So I like to have (the height channels) closer to the center, as do most studios, so that you can localize what’s coming from the ceiling clearer, and what’s the side channels clearer.

— John Traunwieser

Dolby Atmos Height Speakers Placement Recommendations

Gene also recommends a slight modification to Dolby’s spec with regard to the placement of overhead speakers, but while John’s adjustment pushes the speakers closer together laterally, Gene’s has to do with their front-to-back positioning relative to the listener. As quoted above, Dolby recommends a 45-degree angle of elevation from the listening position to the overhead speakers (with 90 degrees being straight up). According to Dolby, there’s some wiggle room there, and anything from 30 to 55 degrees is acceptable. Gene recommends sticking to the smaller end of that range, placing the front Atmos speakers 25 to 35 degrees forward from the main listening position, and the rear ones 25 to 35 degrees behind. (For the record, he also positions them laterally closer together than the spec dictates, just as John does). Gene says that these narrower angles of elevation and tighter formation of overhead speakers result in a more enveloping sound, as long as you’re using speakers with sufficiently wide dispersion.

Dolby Atmos Height Channel Angles

But what happens when you run into obstacles? Maybe there’s a doorway where you want to place a surround speaker, or a light fixture where you want to place an in-ceiling speaker. You might think that these compromises would never affect a professional like John, but even pro mixers live in the real world. The Covid-19 pandemic forced a sea change in the way Dolby Atmos content is created, with many pros setting up home studios and working remotely. By necessity, Dolby even relaxed some of its technical guidelines, allowing mixers to work in studios that weren’t certified using DARDT, the official Dolby Audio Room Design Tool. Perhaps one of the reasons why Dolby gives a relatively wide range of recommended angles for overhead speaker placement is to allow users some flexibility. (Another explanation has to do with the fact that humans are not as sensitive to vertical and overhead location cues as we are to horizontal location cues, owing to the simple fact that our ears are on the sides of our heads.) In any case, how do you proceed when you can’t follow Dolby’s guidelines to the letter? Sometimes you have to place the speakers where you can place them, and at the end of the day, you might still have a pretty good-sounding system. But if you stray dramatically from Dolby’s spec, you will run into problems. John is currently building a home studio, and there’s a fireplace in the room. I don’t recall seeing a fireplace in any of Dolby’s diagrams. Whether you’re building an Atmos mixing studio or an Atmos home theater, these real-world challenges will present themselves. John’s advice is to turn to a professional for help, and that’s precisely what he did. John sought advice from Gene DellaSala and our friendly neighborhood acoustics expert, Matthew Poes.

It’s critical to have a professional know what your room is, and what to work with, and where to place (the speakers). Because the average person wouldn’t know just from typing in dimensions and getting a generic placement for speakers. I’m not (rigidly) following the Atmos spec because I have obstacles that I have to get around, but I have the experience to know, well that’s ok, I can put them here and it will be ok. So there is a wider threshold for putting things in different places. It varies depending on the room size and what you have in there.

— John Traunwieser

Dolby Atmos Q&A with John Traunwieser

During the livestream, viewers had the chance to ask questions and get straight answers about topics that sometimes spark confusion or disagreement among home theater enthusiasts. Some of the questions have been edited for clarity.

Q1. Should a speaker layout match the visual Dolby Atmos renderer on Logic Pro? That is, if the renderer interface shows objects in the corners of the room, do you need speakers in those locations? Is the renderer of Logic Pro showing a valid spatial map of the recording? What about the virtualization of sound between speakers?

John: “Whether it’s Pro Tools or Logic or any other DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), the panner graphic or GUI is just a generic box with dots. It’s not a representation of how your room should be laid out. It’s something that engineers look at to pan whatever, but it’s just a generic box. In Pro Tools it’s a cube, and it just gives you a general idea of where you’re placing something. Ultimately, you’re going to use your ears and pan the sound effect or instrument to the location that you want. So (the GUI) is there as a guide but it’s not showing you what your layout should be.”

Q2. Are there some places where you can’t place objects?

John: “Objects can be placed wherever you want. All of the speakers can be taken advantage of, using objects.”

Q3. Some people advocate placing height speakers high up on the front and back walls. Is that desirable, or should they be on/in the ceiling?

John: “Every single studio I’ve ever been to has Atmos speakers on the ceiling.”

Matthew

Poes added:

Either could be correct, it depends on the angles. The walls make sense if you had very low ceilings. Otherwise, to get the angles right, they would need to be in the ceiling. So, the notion that they should be on the wall, or that that’s the ‘correct’ position (is false). That can work OK in certain circumstances, but that’s not generally the preferred position.

Q4. What are your thoughts about automatic up-mixing in AV receivers?

John: “We always have a fight when it comes to listening to mixes through consumer (equipment) because there is so much additional processing happening in receivers that is undesired, especially when it comes to up-mixing. Because that’s when you’re completely falling off the map of what the original mix was, and essentially you’re remixing it. If you’re watching a 5.1-channel movie but you up-mix it to Auro or Atmos, the box is doing something, and it’s everyone’s guess what it’s doing.”

Q5. Is it important to you that people hear a mix the way it was intended to be heard?

John: “The tools are now available to all the consumers to tweak, and people like tweaking with things. And there are a lot of mixes that sound terrible, and people think they can make them sound better. And sometimes they do sound better. … A bunch of mixers shy away from objects and are very subtle on any Atmos effects, and some go in the opposite direction and put too much content in the surrounds. Yes, you’re an artist when you’re creating content and you have certain freedoms to do wacky things, but it’s ultimately up to people’s tastes. Some may like it, some may not. But I think that’s where it comes down to, if it’s wacky then that was the intention. And if you have it set up right, and you hear the content wacky, that’s how the artist intended it to be. If you “correct” that, then it’s different. It may be better; it may be worse, but it’s different. The thing that I will preface is that a lot of people don’t know if they’re hearing it the way the artist intended, and they’re making critical decisions based on (what they are hearing). That’s what drives us (professionals) nuts. People are like, ‘This sounds terrible, or, ‘Who mixed that? What were they listening to?’ (And yet these people) are not realizing that maybe the AV receiver was having the ‘Concert Hall’ effect on. Or, you’re listening to something that is such a low bitrate that everything sounds compressed, with no dynamic range, sounds harsh. And I would love for people to have the ability to hear it how we hear it, because that is the best experience.”

Q6. What are your thoughts about Dolby Atmos in headphones?

John: “Atmos in headphones is really behind in terms of being able to pinpoint sounds so that you can tell precisely where they are coming from. Using a generic HRTF (Head-Related Transfer Function) doesn’t give you the localization that physical speakers in a room can give.”

Q7. Do you prefer mixing theatrical content, or content for streaming and home theater?

John: “There are mix decisions that I have to make that are compromises to make it translate better to a wider medium. That’s why I like theatrical content the best because it has a stricter standard of calibration and setup. … When it comes to consumer products, there’s so much out there, you can’t possibly make it sound good on everything.”

Q8. How important is system calibration? Can one calibration be used for all formats and source components?

John: “Not all the content you’re listening to is in Atmos. You could be listening to 5.1 or 7.1 content through your Atmos system. And if you want to get very granular, if you want to hear it as the director intended, technically you should have different calibrations for different formats. The bass management is different for Atmos and Imax and 5.1/7.1. In a properly calibrated room at 5.1/7.1, the surrounds are down 3dB, so they should be 82dB, not 85dB. When you’re calibrating an Atmos room, everything is at 85dB, so you’re already hearing the surround speakers 3dB louder than they should be (when listening to 5.1/7.1 content). Even going back and forth between an Apple TV and a Kaleidescape, I can’t use the same calibration because they don’t sound the same.”

Q9. You’ve mixed in lots of different studios. Do they all use a standardized Atmos setup?

John: “It’s still the Wild West in studios. Depending on which studio you go to (for mixing), it can be a different configuration.”

Conclusion on Dolby Atmos Best Setup Practices

We’d

like to thank John Traunwieser

for sharing his knowledge and insight. We hope that this discussion helps our

readers understand how Atmos works, and how that informs the best way to set up

a Dolby Atmos home theater. If you STILL need help with your Dolby Atmos Home theater, you can always do a one-on-one home theater consultation with Gene DellaSala, or you can

contact Matthew Poes about acoustic optimization and setup of home studios,

dedicated listening rooms, and home theaters.