Is the Romance of High Fidelity Audio Today Dead?

“You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin’ ”

-- Righteous Brothers, 1964

The hobby of high-fidelity is fascinating. You have to understand, this is a singularly individual hobby, like no other. Audiophiles who came ‘of audio age’ in the Golden Era of the 1960’s-1980’s had a relationship with the equipment and aura of audio that simply doesn’t exist today. Certainly not to the same degree, anyway. Today’s equipment—whether it’s a multi-channel theater setup or a 2-channel music purist system—is so uniformly excellent that a lot of the mystique and “skill” of picking out one’s personal system is just not there anymore. That skill is not needed. Speakers, amplifiers, music-delivery devices, they’re all so good these days. The era of blind-luck, hit-or-miss design has long since passed.

Consider that 40-60 years ago, this is how it was:

Audiophiles

actually put together their music-playing system one component at a time. They

chose the electronics of the system, they selected the turntable, they chose

the actual cartridge and the speakers. This was known as a “component” system

because the audiophile picked out every component themselves, based on reviews

they’d read, speakers they had heard and liked, other audiophiles they’d spoken

to and the recommendations of salespeople in the stereo store.

Audiophiles

actually put together their music-playing system one component at a time. They

chose the electronics of the system, they selected the turntable, they chose

the actual cartridge and the speakers. This was known as a “component” system

because the audiophile picked out every component themselves, based on reviews

they’d read, speakers they had heard and liked, other audiophiles they’d spoken

to and the recommendations of salespeople in the stereo store.

There is nothing like that today. Let’s say you want a toaster oven for your kitchen. You go to Walmart or look on Amazon, find one that looks nice for the price you want to pay, and you get that one. Pretty simple.

But….let’s imagine you’re really into toaster ovens. You’re passionate about them. You read everything you can about them. You’re a total expert on everything there is to know about toaster ovens. So, here’s what you do: You evaluate and compare six different sets of heating elements. You compare how hot they get, their expected lifespan, their physical size, their “speed to maximum heat” time, etc.

Then you look at aluminum enclosures. Same thing—you evaluate and compare their size, construction method, hinge assembly action, price, knobs, temperature adjustment range, heating options (bake, toast, broil, keep warm—does it have all those? Do you need/want all those?), etc.

But wait, you have to look at tempered glass fronts for the door: tint color, heat resistance, breakage resistance, thickness, opacity, cost, size, availability.

Then you assemble your chosen components into one complete, customized-just-for-you toaster oven system. It’s the best toaster oven for the money ever—because you designed it and put it together.

That’s

what a component hi-fi system was in the 1960’s through 1980’s—every individual

component was selected by the audiophile. No two systems were alike. Every

system was a reflection of that person’s likes, tastes, biases, influences,

etc., all tempered by their budget and the space in their den or living room that

was available to fit the system. You’d go over someone else’s house in the

1960‘s or 1970’s and guys’ eyes would instantly dart to that homeowner’s hi-fi

system. “Oh,” the visitor would think to themselves, “They have a Pioneer

receiver, the SX-727. Not bad. But I have AR-3a speakers and he only has KLH

6’s. My system’s better.”

That’s

what a component hi-fi system was in the 1960’s through 1980’s—every individual

component was selected by the audiophile. No two systems were alike. Every

system was a reflection of that person’s likes, tastes, biases, influences,

etc., all tempered by their budget and the space in their den or living room that

was available to fit the system. You’d go over someone else’s house in the

1960‘s or 1970’s and guys’ eyes would instantly dart to that homeowner’s hi-fi

system. “Oh,” the visitor would think to themselves, “They have a Pioneer

receiver, the SX-727. Not bad. But I have AR-3a speakers and he only has KLH

6’s. My system’s better.”

Those are alien considerations today. Two 20-year-old guys arguing over which speakers were best in the college cafeteria doesn’t happen anymore. Heck, walking into a stereo store doesn’t happen anymore, never mind getting involved in some knockdown-drag out fight with a smarmy, opinionated store salesguy who wanted to sell you only EPI speakers, even though you insisted on hearing the Advents, because your roommate’s Small Advents sounded so good to you.

Then, a little later on, those 20-year-old college kids graduated school, got decent-paying jobs and kept their interest in audio gear. They became audiophiles. Stereo Review, High Fidelity and Audio magazines cluttered up their coffee table, in spite of their wives’ insistence to clean them up and put them away.

Once audio equipment was in your blood, it was there to stay. You always wanted to upgrade, to add on something new. You thought about the next discretionary $400 that would come your way. The next decent chunk of change that you could spend, guilt-free, without your wife accusing you of taking food off the table. What would it be? Add a cassette deck to your system? Maybe a graphic equalizer? Maybe you could trade in your 12-year-old Large Advents that you had since your Junior year for something really good, like AR-91’s. If they gave you a reasonable trade on the Advents and a deal on the AR’s, $400 should cover the difference. Maybe you’d just add $100 (in cash, of course) if needed and not say anything…..

The thing about that great old audio gear was that it held an emotional attachment, as opposed to being merely functional. You selected that individual model number, after painstaking research, comparison shopping, seeing your friends’ systems, going around to all the stores, touching it, listening to it, spinning the dials, flicking the switches, taking the grilles off.

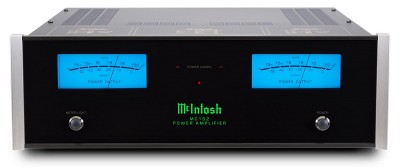

There was definitely a romance to the process. Seeing the back-lit blue power meters on a McIntosh power amplifier and imagining it in your system, in your living room, powering your speakers, you just knew it would sound great. Look at that thing: those heatsinks! The amp weighed a ton! That power supply—toroidal! It just has to be so much better than your Pioneer receiver.

In the 1970’s, receivers had analog FM tuners. You tuned to a station by turning a weighted central tuning knob, connected by an internal string to the tuning pointer. Since this was the primary point of user interaction with the unit, manufacturers figured out pretty quickly that if they made the feel and action of the tuning knob silky-smooth and precise, it would go a long way towards conveying quality, by virtue of great tactile sensation. Unlike the tuning knobs on FM tuners in the 1960’s (which felt like garden-variety table radios), tuning knobs in the 1970’s were fabulous. You could take a heavily-weighted Pioneer tuning knob on, say, an SX-838 receiver from 1974 and spin it all the way from 88.1 to 106.9 in one easy action. Man, that was impressive! That was equipment romance at its best.

Cassette

tape decks from that time period had smoothly-damped door mechanisms. You

practically needed a stopwatch to time how long it took for the door to open,

it was so slow and smooth. Turntables too: The best ones had cueing levers that

raised and lowered the tonearm with such incredible precision, it was a joy to

behold. If they were fully- or semi-automatic devices, the tonearms and

platters moved and spun like fine machinery. The German-built Miracord 50H II

automatic turntable actually had a disc brake on the platter that would bring

it to a smooth stop at the end of the record. You could hear the quiet,

background noise “shhhhh……”of the brake engaging the platter. It was the sound

of finely-engineered German machinery at work. My older cousin had a 50H. I

think he liked the sound of that brake more than the sound of the Coltrane

record that had just finished playing! These components just exuded romance.

Interacting with them, the pride of ownership at having made the very personal

decision to acquire that particular model over all the others you could have

chosen, made the hobby of audio from the 1960’s through the 1980’s something

very special indeed.

Cassette

tape decks from that time period had smoothly-damped door mechanisms. You

practically needed a stopwatch to time how long it took for the door to open,

it was so slow and smooth. Turntables too: The best ones had cueing levers that

raised and lowered the tonearm with such incredible precision, it was a joy to

behold. If they were fully- or semi-automatic devices, the tonearms and

platters moved and spun like fine machinery. The German-built Miracord 50H II

automatic turntable actually had a disc brake on the platter that would bring

it to a smooth stop at the end of the record. You could hear the quiet,

background noise “shhhhh……”of the brake engaging the platter. It was the sound

of finely-engineered German machinery at work. My older cousin had a 50H. I

think he liked the sound of that brake more than the sound of the Coltrane

record that had just finished playing! These components just exuded romance.

Interacting with them, the pride of ownership at having made the very personal

decision to acquire that particular model over all the others you could have

chosen, made the hobby of audio from the 1960’s through the 1980’s something

very special indeed.

Much of today’s equipment does not exhibit—nor does it even try to—that same degree of flat-out romance and visceral appeal. Many of today’s amplifiers—whether integrated amps, multi-channel AVRs or totally inclusive home systems like smart speakers or Sonos-type whole house music systems—are powered by Class D amplification. That is absolutely the correct design decision for these units. The actual audio performance of modern Class D amplification is excellent and their advantages over Class AB amps in terms of space and weight efficiency is huge.

Today’s audio/home entertainment customer (those under, say, 40 years of age) simply don’t have the same expectation and interaction experience with home equipment as do older enthusiasts. Some do, of course, but not as a general rule. Having grown up on a steady diet of smart phones, tablets, ear buds, fast Internet access, smart speakers, etc, today’s younger audio buyer is what could be characterized as results-oriented. How does the unit/system perform? Do I get what I want quickly, conveniently, repeatedly? Yes or no? It’s the result that they are looking for, every time, no questions asked.

The audiophile from the 1960’s-1980’s (and the small slice of traditional audiophiles who are still out there) are as much process-oriented as they are results-oriented. For them, the actual process of researching, auditioning, selecting and assembling their hi-fi systems was as important as the final result of listening to their system. Indeed, for the old-time audiophile, the process never ends, since they are continually on the hunt for their next upgrade, their next tweak, their next improvement.

So, it’s a “Results vs. Process” audio universe. Embedded deeply, inextricably in the “process” aspect of this hobby is the notion of the romance, the visceral, emotional appeal of the equipment. It’s doubtful that the average home audio buyer under 40 will ever feel that thrill when seeing backlit power meters glowing in the dark or a row of cast-aluminum heatsink fins bristling like a battleship’s 16-inch guns from the sides of a monstrous 500-watt RMS power amplifier.

Audio, you’ve lost that lovin’ feelin’.

Article Epilogue

by Gene DellaSala

It is interesting to read Steve's romanticism of audio gear from the 60s to 80s. I find myself of a similar mindset of audio gear from the 80s to early 2000's. I dearly miss going to local hifi shops to demo and touch the gear I was interested in purchasing. Making a purchase online is just not the same. I wrote about the best home theater receivers of all time and of a strong mindset that the golden age of that category of product ended with the demise of the super receivers in the early 2000's. I'm in agreement with Steve that audio gear performance is more predictable today (especially with loudspeakers) than decades ago making it easier to build systems that sound good with less trial and error. However, the streamlined selection process and reduced shelf life caused by new technologies emerging at substantially more rapid rate has certainly made us value the components we select less than ever today. Food for thought.

Do you still have that lovin' feelin' for audio gear? Share your comments in the related forum thread below.