Stereo Gear in the 1970’s Was it The Audiophile Golden Age?

There are times when circumstances and conditions come together in a once-in-a-lifetime manner, right? You know what I mean—perhaps it is a sports team, when just the right collection of players are on the team together, their personalities and chemistry mesh perfectly and they’re all having great seasons at the same time. Or it could be a job, when market conditions are ideal for your company’s offerings and you have just the exact personnel in place that can do the job. Maybe it’s a social situation, when the setting is just right, your feelings are right, you know exactly what to say—not too nervy and not too forward, but sufficiently confident and chance-taking—such that you make that all-important connection that will alter your life.

For the market of high-fidelity electronics and speakers, that time was the 1970’s. Things came together in such a way that the market flourished and grew like never before. It was a singularly great time for the industry, with all the historic, demographic and technological conditions and advances coming together in a way that will never be repeated.

Let’s take a closer look at the significant factors that made the 1970’s so special for audio and how and why those factors affected the stereo industry in the ‘70’s.

American History

I’ll try not to veer too far off the audio path here, but the country’s historical context is important in order to put the 1970’s audio market in its proper perspective.

Following the successful conclusion of World War I (1914-1918), American entered a period of great economic and social expansion. Known as the “Roaring Twenties,” this was a great time for our country. The mood was celebratory, the economy was strong and the prospects for the future seemed limitless.

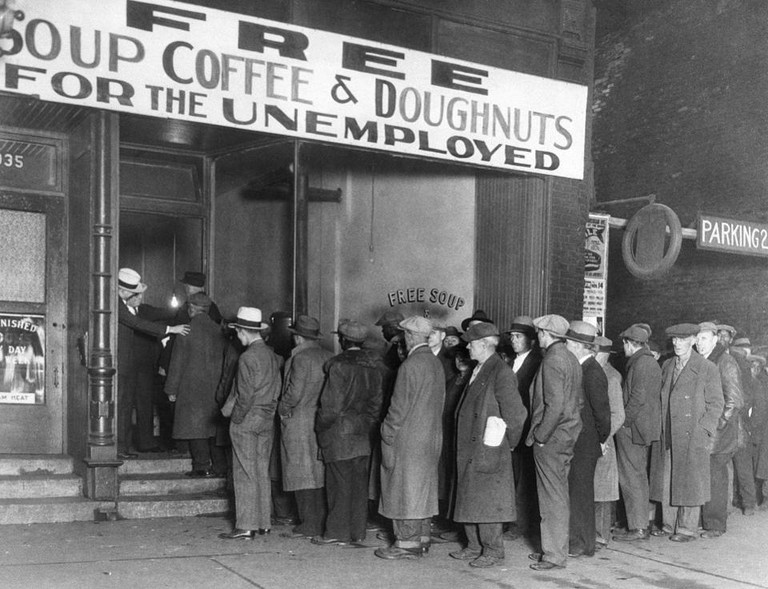

Then in 1929, fueled by a series of disastrous Federal decisions with respect to interest rates and the money supply, the stock market crashed in dramatic fashion on October 24th, 1929 (“Black Thursday”), plunging America into the Great Depression, the likes of which had never been seen before and would never be seen again. Unemployment soared to nearly 25% and remained well into double-digits for more than an entire decade. Even President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s much-heralded “New Deal” package of Government spending and assistance programs couldn’t pull the country completely out its economic funk. As late as 1938—fully five years after the New Deal and nine years after the Depression began—unemployment was still 19% and the country’s economy was a total wreck.

The Great Depression, 1929-1941

With America’s entry into World War II following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the nation’s armament factories shifted into high gear, as millions of people went back to work and off to fight overseas. When WWII ended in 1945, the millions of returning GI’s got new jobs, started their families and built the greatest economy the world has ever seen. With the demand for housing skyrocketing, the suburbs exploded and the construction and home furnishings markets flourished commensurately. Automobile production—shuttered completely for the four years of the War (1941-1945)—jumped back to life in the face of incredible pent-up demand. Television took hold and made its way into homes across the country. The stage was set for the post-WWII period to be one of the most explosive economic expansions in our country’s history.

Market Demographics

The overriding sentiment of all these new young WWII veteran families was this: “I’m going to provide my children with the opportunities and comforts that I never had when I was growing up in the Depression.”

Thus started the Baby Boom Generation, children born to WWII vets, from 1946-1964. The very heart of this group—those born from 1948 through 1961—was in college at some point in the 1970’s, away from home, going to concerts, partying and hanging out with their friends.

Remember, in the 1970’s there was no Internet, no e-mail or texting, no Social Media, no smart phones, no Amazon, no personal computers or laptops or tablets, no Playstation, nothing of that sort. But….it was a great, great time for popular music: The Stones, Led Zeppelin, The Grateful Dead, Santana, The Allman Brothers, Pink Floyd, ELP, Stevie Wonder, Chicago, Fleetwood Mac, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Steely Dan, The Who and dozens of others attracted concert-goers and album buyers by the millions.

It was also a time of tremendous technological advancement (which we’ll detail below) in the audio industry. When you combine the market forces that were in existence at the time—a period of great economic and social activism and engagement, the largest demographic bubble (the Boomers) the country had ever seen, the attendance at college by millions of young people, which had never happened before, coupled with large sums of disposable income, music playback equipment that was both quite good and easily affordable (and as we’ve said, without significant competition from other technological distractions)—all the puzzle pieces were in place for a “perfect storm” of unprecedented audio market growth.

Baby Boomers are voracious consumers

Technological Developments

With the

historical and demographic stars now properly aligned, all that was needed to

complete the circuit, so to speak, was the right audio equipment. If the

manufacturers could engineer and deliver audio playback equipment that was

high-performance, reliable, good-looking and affordable, then the Baby Boomer market

was ready to buy, in big numbers. It was all up to the audio companies now.

With the

historical and demographic stars now properly aligned, all that was needed to

complete the circuit, so to speak, was the right audio equipment. If the

manufacturers could engineer and deliver audio playback equipment that was

high-performance, reliable, good-looking and affordable, then the Baby Boomer market

was ready to buy, in big numbers. It was all up to the audio companies now.

And they delivered. Big time.

The first thing that had to be accomplished was the design and manufacture of inexpensive, reliable, high-performance audio amplifiers. If receivers and integrated amplifiers couldn’t deliver full power at low distortion all the way down to 20 Hz, then the Boomers wouldn’t be able to blast out their favorite group’s latest album at chest-thumping, lifelike SPLs.

The development of the direct-coupled output stage achieved that. I remember around 1971, a new series of Panasonic-branded receivers (about a year before they came up with their “Technics” brand marketing angle for their high-fidelity division) were advertised as having direct-coupled amplifier sections, resulting in flatter frequency response into the lowest bass range, at full power and lower distortion than had previously been possible with traditional capacitor-coupled designs. Pioneer (with the SX-424 through SX-828) and Kenwood (with their KR-5200, 6200 and 7200) soon followed suit and the availability of truly full-range, low distortion amplifiers made really satisfying audio reproduction—deep, pounding, clean bass, essential for the day’s sought-after rock music—possible for the first time at affordable prices. With this new generation of receivers and amplifiers, audio electronics transitioned from the realm of the 1950’s-60’s suburban middle-aged “GE engineer/Big 8 accountant”-type customer to being a staple for the 1970’s college kid who’d saved up his/her summer job money and was ready to spend.

Lots of other good developments in audio in the early ‘70’s coincided with the direct-coupled-equipped receivers:

Around the same time, really excellent, affordable speakers like the Large Advent, AR-2ax, Infinity 1001 and EPI 100 became available and great music with pounding bass and clear highs was blaring in dorm rooms from coast to coast.

Turntables like the Dual 1215 and 1218 and the really good, rugged Pioneer belt-drive manuals fitted with good-sounding cartridges from brands like Shure, Audio-Technica and Stanton made record playing simple, accurate and reliable. Technics introduced the revolutionary SL-1200 in late 1972, the industry’s first direct-drive turntable. In the 1970’s, you didn’t have to spend a fortune to get a really excellent turntable.

The Cassette Tape

One of the most

significant audio milestones of the 1970’s was the appearance of the cassette

tape player/recorder equipped with Dolby B noise reduction.

Back in the days before portable audio was commonplace, the

dominant playback formats were the vinyl LP and reel-to-reel tape. Both were

perfectly acceptable playback media, with good fidelity and reasonably

wide-range sound. Vinyl LPs were a bit restricted as far as their ultimate

low-frequency extension was concerned (deeper bass meant wider grooves, which

reduced the playing time that could be fit onto a record), and LPs had their

well-known signal-to-noise issues, especially in regard to surface noise, pops,

clicks, etc.

Open reel tape was far superior to the LP in terms of both frequency response

and signal-to-noise ratio, but it was incredibly cumbersome and inconvenient to

use in the home, and the medium did not lend itself at all to selling pre-recorded,

finished material.

In the mid-1960s, Phillips developed and introduced a miniature tape recording

system called the Compact Cassette. Using a very narrow magnetic tape (about

1/8-inch wide, whereas most good reel-to-reel tapes were at least 1/4-inch wide),

it was housed in a plastic shell that could simply be popped into the player—no

actual handling or threading of the tape was required. It was incredibly simple

to use and quite small—roughly the size of a pack of cigarettes. When it was

introduced, Phillips intended it strictly as a low-fi medium, for dictation and

other non-critical uses. Wide-range frequency response and impressive

signal-to-noise ratio were not design considerations.

However, good marketing people always have their eyes open for the next big

opportunity. People immediately recognized that the cassette (no one used

“Compact”) had tremendous potential as a viable, simple-to-use high fidelity

recording format, perfect for either home or portable/automotive use. The only

potential roadblock was its terrible sound. Other than that, as they say, it

was perfect.

Then, clever and innovative engineering people entered the scene. The

manufacturers quickly developed transport systems with stable, dependable

motors that ensured accurate tape speed and long-term reliability. Tape

manufacturers came up with a new formulation called CrO2 or chromium dioxide.

“Chrome tape,” as it was called, had markedly better recording properties than

standard tape. High frequencies were vastly superior, distortion was much

lower.

But….there was still one critical puzzle piece missing: Noise. The low tape speed of cassette (1 7/8 Inches Per Second or IPS compared to open-reel’s 7 ½ or 15 IPS) meant that the background noise floor inherent in the magnetic tape medium was simply too high in the cassette format to be acceptable in high fidelity applications. If the cassette’s noise issue couldn’t be satisfactorily ameliorated, then it had no future in the “serious” audio business.

The issue was solved. Here’s how:

Dolby Noise Reduction

Dolby

Labs, founded by Ray Dolby in the 1960s, developed and introduced a series of

tape-recording noise reduction systems that improved the inherently noise-prone

recording process of magnetic tape. The first system was called Dolby A, and it

was intended mainly for professional recording applications.

But the system that really had the biggest impact on the consumer electronics

market was Dolby B. This was a simple but extremely clever “compander”

(compression/expansion) system, whereby the signal above around 1kHz would be

pre-emphasized (boosted in level) during the recording process and then

de-emphasized back to its correct level upon playback. Since the inherent noise

floor of the tape was always there, when the 10dB playback de-emphasis took

place, the tape’s residual hiss level was reduced by that 10dB as the original

signal was played back at its correct level. It was simple and ingenious and

soon became a widespread industry standard.

People would ask for it by name, even if they had no actual technical

understanding of its function: “Does it have Dolby?” “I want

Dolby.” “This is good, it has Dolby.” When people ask for a specific

technology by name and base their buying decision on whether or not the product

has that technology, that is proof of the importance it has to that market.

Advent Corporation of Cambridge MA introduced a cassette deck in 1971 that

combined these new technologies—Dolby B noise reduction and chrome tape

capability—into a brand-new model, the famous Advent 201 cassette deck. With

the ability to make truly high-fidelity, great-sounding tape recordings combined

with the small size and convenience of the cassette’s form factor, the 201

ushered in a new chapter in home audio. High-quality cassette units soon

followed from all the major manufacturers like Pioneer and the cassette became

a major fixture in consumer electronics—in the home, the car and in portable

devices like the Walkman and the boombox— for at least the next two decades.

Even today, there are millions of cassette-equipped cars still on the road,

satisfying their drivers with surprisingly good sound. But it all started in

the pivotal, never-to-be-repeated era of the 1970’s.

Late-70’s Pioneer cassette deck

Power Rating Confusion and Resolution

With the college-aged Baby Boomers buying up stereo equipment at an amazing pace, the manufacturers took to advertising their amps and receivers in truly outlandish, misleading ways with respect to wattage power ratings. It got so bad, that in 1974, the Government stepped in with their now-famous “FTC Power Ratings” ruling. To my mind, this was one of the few times when Government intervention actually helped a situation, instead of making it worse. Here’s the full story, as I’d written before in The Golden Age of Audio:

The 1974 FTC Power Ratings mandate:

As stereo grew in popularity by leaps and bounds through the 1960’s, the electronics manufacturers began to inflate and exaggerate their amplifier power ratings in a blatant attempt to win the attention of prospective new customers. Things got so bad (30 watt-per-channel RMS amplifiers were being advertised as having “240 watts of total system musical peak power!”) that by 1974, the Federal Government had to step in with amplifier rating guidelines to ensure that the manufacturers rated their equipment honestly.

One of the new guidelines was a 1/3-power “pre-conditioning” requirement, which stated that amplifiers had to be run at 1/3-power at 1000Hz for an hour before the power output and distortion measurements could be made. The rational, presumably, was that an amp that was properly “warmed up” would give a more accurately representative result than an amp that was measured “cold.”

The problem was this: the 1/3-power test made a class AB amplifier (which virtually all the amps were at that time) run very hot—especially at 4 ohms. Manufacturers found that they had to either modify existing equipment to increase the heatsinking or downgrade their power ratings so they’d run cooler at a lower power level. The very popular Dynaco SCA-80 integrated amplifier, for example, was downrated from 40 watts RMS/channel to 30 watts after 1974.

For new equipment, the answer was simple: Simply don’t rate the amplifier at a high power level into a 4-ohm load, since a 4-ohm load required too much expensive, heavy heatsinking, a beefy power supply and heavy-duty output transistors. Things were very competitive in the stereo biz and every dollar counted. If a manufacturer could save $10-20 by using less of that costly die-cast aluminum heatsinking, a less beefy power supply and cheaper, less robust output devices, that could easily translate into a retail price that was $50-100 lower. In a cutthroat market, there’s a world of difference between a receiver priced at $279 when your biggest marketplace rival is $369.00.

Regardless, in the 1970’s, amps and receivers could routinely handle 4-ohm loads. There were some really great lower-priced units that were pretty gutsy. The Sherwood S-7100A could deliver 20-25 watts per channel into 4 ohms all day long and the entry-level Pioneer SX 424 and 525 were also quite comfortable with 4-ohm speakers. A very popular 4-ohm “budget” speaker in those days was the Smaller Advent Loudspeaker. “Small Advents,” as they were called, were deliberately designed to be 4-ohm speakers. Advent wanted the Smaller Advent to have essentially the same excellent bass response and deep extension (-3dB in the mid-40’s Hz) as the Large Advent. In order to achieve this, they needed a woofer with more mass (they mass-loaded the center of the woofer, under the dustcap), for a lower free-air resonance to offset the smaller volume of air in its compact cabinet. It worked just fine, but at a severe penalty in sensitivity—the Small Advent needed a lot of power to drive to reasonably loud levels. To offset that, Advent made it a 4-ohm speaker, so it would draw more power out of its companion receiver and “seem” just as loud for any given volume control setting as the bigger Large Advent, which was an 8-ohm speaker.

Sherwood S-7100A receiver—1972

This was clever engineering and marketing on Advent’s part, made possible only because modestly-priced receivers and integrated amplifiers existed at that time that could handle 4-ohm loads. There were thousands of Small Advents and Sherwood receivers happily signing away in dorm rooms all over the country in the 1970’s. Today’s inexpensive, entry-level electronics generally caution against using 4-ohm speakers. It’s usually not until you get into the middle-range models that low-impedance loads are acceptable (and then often only 6-ohm). But in the 1970’s, 4-ohm loads were perfectly acceptable for inexpensive electronics.

There were record stores everywhere and in areas with strong concentrations of college-aged kids—like Boston, NY, Chicago, Los Angeles, etc.—it seemed like there was a stereo store on every street corner. Tech Hi-Fi, Tweeter Etc, Audio Labs, DeMambro Electronics, Atlantic Sound—these were just some of the store names that I can recall. Indeed, as a college kid in Boston in the mid-70’s, I remember there were no less than four stereo stores (and at least as many record stores) in Harvard Square in neighboring Cambridge, a trendy retail/dining section not bigger than a mile by a mile. I spent many a Saturday buying jazz albums and going from store to store, looking at all the new gear and bugging the salespeople.

Tower

Records—a fixture in the LP’s heyday

The Receiver Becomes King

As the stereo market exploded in size among the college-aged consumer in the ‘‘70s, receivers became the dominant electronic component, replacing the separate preamp/power amp configuration that was popular among the middle-aged audio enthusiasts who comprised the majority of the market in the ‘50s thru mid-‘60s. Advances in electronic componentry, such as the widespread availability and low cost of reliable silicon transistors, made the design and manufacture of budget-priced receivers feasible and popular. By combining three components—the power amplifier, preamplifier and tuner—onto a single chassis, using a single main power supply and only one cabinet, the manufacturer’s cost of production, shipping and warehousing was drastically reduced. Receivers were eminently affordable by college kids, reliable (many a beer was spilled into them!) and they boasted high performance, the likes of which would have been unthinkable only ten years prior.

Vintage Pioneer SX-727 Receiver

The decade of the 1970’s was unquestionably the Age of the Receiver (and to a large extent, the age of the Integrated Amplifier as well. I am actually still using a 50 WPC 1972-vintage Kenwood KA-7002 integrated amplifier in one of my systems right now. It’s 49 years old, works perfectly and sounds great). And what a Golden Age the 1970’s were. Every year, major manufacturers like Pioneer, Kenwood, Sony, Sansui, JVC, Marantz and Sherwood introduced new and better models, with more features, more power, and lower prices. There seemed to be no end to the growth and success of the audio market, so the manufacturers flourished and consumers benefitted from better and better gear at lower and lower prices.

Kenwood KA-7002 Integrated Amplifier 50/50 WPC

That Elusive 100 Watts per Channel Barrier

However, there seemed to be an “unspoken” barrier to power ratings, a level that, for whatever reason, no manufacturer of receivers or integrated amplifiers wanted to cross: The mysterious 3-digit barrier, the 100-watt per channel line in the sand. Around 1970 there was the Crown DC300 power amplifier, a brute of a power amp, rated at 150 watts per channel. This was probably the first truly high-powered consumer amplifier, but it was a power amp, not a receiver.

Crown DC 300 150 WPC power amp of 1970

For receivers, the 3-digit barrier seemed like an impenetrable wall, almost foreboding and sinister, as if something horrible would befall anyone who had the nerve to attempt it. It was almost like the fear that aviators had in 1947 about breaking the sound barrier before Chuck Yeager did it in the Bell X-1. There was the safety of 40, 50, 55, 70 watts per channel. But no one dared to go to…..<gulp>….100. Remember, too, in those days 60 watts per side was considered more than enough, especially since the reputable manufacturers in those FTC days were rating their equipment honestly and conservatively. It was a competitive badge of honor to see how far you could surpass your “published specs” in a review in a major magazine, then quote the reviewer in your next print ad saying something like, “The Kenwood KA-7002 easily surpassed its rated power specifications on our test bench, clocking an excellent 63 watts compared to its rating of 50 watts,” said Stereo Review. In 1974, 60 watts RMS was a really, really gutsy 60 watts RMS.

Because the FTC got involved with advertised power ratings in 1974, wattage wasn’t faked or fudged. It wasn’t one-channel driven or two channels driven out of seven, or 1kHz or at clipping/1% or 10% THD or any other bogus arrangement like the majority of manufacturers do today. Let’s be totally honest here: In the 1970’s, 1% THD was not high fidelity. 1% THD was low-fi, it was a joke. Heck, a power rating of 1% THD at 1kHz would’ve been laughed out of the joint as being completely unacceptable for serious gear. Because rating power at 1% THD at 1kHz is a joke.

No, instead, in the 70’s, power ratings were the real deal. We’re talking Class AB amplifiers here. Power supply and heatsink weight tell a large part of the story. A good integrated amp or stereo receiver from the mid-70’s rated at 60/60 watts RMS weighed in at about 30 pounds. Today, a typical Class AB 7.1 channel home theater receiver rated at “7 x 100 watts” weighs about 35 pounds, even with all the extra channels of amplification and the HT circuitry. How is that even remotely possible? It isn’t, of course.

Side observation: Audioholics tests amplifiers and receivers in a very stringent, transparent and professional manner. The results from one test can be easily compared to another and the consumer benefits from clear, accurate data. The manufacturers and the FTC should take note, especially since the 1974 FTC power rulings are no longer in effect in today’s multi-channel age.

Pioneer Led the Way in Receivers

So in 1974, 100 watts per channel had to be All Channels Driven, 20-20kHz, at a very specific and very low level of THD. Not easy, especially in 1974. Pioneer did it with their groundbreaking SX-1010 receiver, the industry’s first-ever 100 WPC receiver.

And what a beautiful, full-featured, great-sounding piece of gear that was! It had very innovative tone controls with “turnover frequencies” that enabled the user to adjust the frequency extremes without affecting the midrange. Like almost all 1970’s FM tuners, it was analog, but in typical Pioneer fashion, the tuning dial was heavily weighted and perfectly balanced, giving it a luxurious, precision feel as you spun the knob from one end of the tuning scale to the other.

The groundbreaking Pioneer SX-1010 100 WPC receiver

The SX-1010 opened the power floodgates. Once Pioneer introduced the 1010, everyone else rushed in with their own 100 watt receiver. Soon, 100 WPC wasn’t enough. It went to 105, 110, 125. The “power race” was on.

Pioneer’s next family of receivers, the SX-x50 series, upped the ante with the 120 WPC SX-1050 and the terrific 160 WPC SX-1250. These were truly beautiful units, with their all-silver faceplates and amber-backlit tuning dials. They had great amps, capable of driving low-impedance speakers in their sleep, low-noise pre-amps with those great tone controls and fabulous FM tuners with Pioneer’s phase-locked loop circuitry, during an era when pulling in over-the-air FM broadcasts was really important.

Marantz, Kenwood, Sansui, Sherwood, Technics and others all had similar competing high-powered receivers, all great-looking, superb performers, all built like tanks. This was an amazing period for stereo receivers. Today, any of these units—and there are many sites that will fully refurbish them and restore them to factory-original specs—sell for astonishingly high prices. If you can find them, that is. They sell as fast as they become available.

Pioneer was the market leader in receivers. They led the way, they established the benchmarks and set the standards. Everyone else seemed to take a “see what Pioneer does” approach to the receiver market. The family of receivers that followed their SX-1010 really cemented Pioneer’s leadership in receivers and integrated amplifiers. I’m not saying that Pioneer was the absolute best sounding, most audiophile-worthy brand out there, but they were definitely the pace-setters for styling, features and power.

Nothing illustrated this better than the incredible SX-1250 receiver. Introduced in 1976), it was rated at 160 watts RMS per channel, 20–20kHz, at .1% THD. Not .5% or even .25% (McIntosh’s old claim-to-fame), but .1% THD over the full 20-20kHz bandwidth.

Pioneer SX-1250 Receiver

The SX-1250 single-handedly heralded in a new chapter in receiver history: the era of the ultra-high-powered receiver. Soon after, 160 watts was hardly enough to even get into the game. The SX-1250 was replaced by the SX-1280 in 1978 which boasted 185 watts per channel, not at .1% THD over the 20–20kHz bandwidth, but .03% THD. Rated, advertised, guaranteed—.03%!

Then in 1979, Pioneer introduced the totally off-the-charts SX-1980, which raised the bar to 270 watts RMS per channel, 20–20kHz, at .03% THD. It weighed a ridiculous 80 lbs. It was 20 inches deep. It wouldn’t fit in any sane person’s entertainment furniture.

But the biggest, heaviest, most powerful two-channel receiver I ever knew about was the Technics SA-1000. It boasted 330 watts RMS per channel 20–20kHz. .03% THD. It was even bigger and heavier than the Pioneer SX-1980. I never actually saw one in person and I can’t vouch 100% that it actually materialized in the flesh on dealer shelves. But they announced it, so that sort of counts, right?

Technics SA-1000 Receiver

And then, mercifully, without any warning or real reason, it was over. The receiver power race that Pioneer started with the 100 WPC SX-1010 finally came to a peaceful, anti-climactic end. But it sure was fun while it lasted! Like long sideburns, polyester leisure suits with wide lapels and bellbottoms, the high-powered receiver was oh-so “70’s.”

High-Powered Music to go with High-Powered Receivers

There is a very interesting musical

development that coincided with the 1970’s receiver power war. That was the

emergence of jazz-rock fusion music, often referred to by musical insiders as

“high energy” jazz. In almost exact chronological lockstep with the advent of

the high-powered receiver came the emergence of high-energy jazz-rock fusion

music. Groups like John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report,

Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters, Miles Davis’ electric band, Chick Corea’s incredible

Return to Forever, Larry Coryell’s Eleventh House and others blasted onto the

musical scene in the early 1970’s.

There is a very interesting musical

development that coincided with the 1970’s receiver power war. That was the

emergence of jazz-rock fusion music, often referred to by musical insiders as

“high energy” jazz. In almost exact chronological lockstep with the advent of

the high-powered receiver came the emergence of high-energy jazz-rock fusion

music. Groups like John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report,

Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters, Miles Davis’ electric band, Chick Corea’s incredible

Return to Forever, Larry Coryell’s Eleventh House and others blasted onto the

musical scene in the early 1970’s.

These bands—with their amazing high-volume refrains, pounding rhythmic basslines and searing lead guitars—appealed to both hard-core rockers and cerebral jazzers, routinely playing to sold-out venues. Anyone who attended a Mahavishnu Orchestra concert in the ‘70’s remembers it being more like a spiritual happening than a mere pop music concert. It would begin with a totally darkened hall, then the audience would light matches (no 2021 safety regs in those days!), holding thousands of them up as the musicians walked onstage. As the matches were extinguished, McLaughlin would begin the opening strains on his distinctive double-neck guitar, and the rest of the band would follow. Thus began a Mahavishnu Orchestra concert—a continuous, uninterrupted 120-minute blur of unequaled musical pyrotechnics and emotional intensity. I was always struck by how much their drummer Billy Cobham—a drummer whose sheer speed and technical brilliance has never been surpassed, to my ear—reminded me of then-heavyweight boxing champion Joe Frazier: Both men were physically stocky and thickly muscled, full of seemingly boundless frenetic energy and non-stop motion.

Like the high-powered receiver, high-energy jazz-rock fusion bands faded from prominence by the end of that decade. It could be that the perfect alignment of high-energy jazz-rock fusion music in the 1970’s with the high-powered receiver race in the 1970’s is just one of those inexplicable coincidences, two totally unrelated, independent phenomena. It probably is, the more I think of it. But it’s a delicious happenstance, with both developments destined never to occur again and both being immensely enjoyable to the largest demographic group of music lovers/stereo buyers the country has ever seen. And will ever see.

“Speaker Wars” in the 1970’s

There were other only-1970’s social experiences that took place with stereo equipment. One of my favorites was the common practice of waging “Speaker wars” with your friends. When we were in high school and college, we all had our first component stereo systems. The most critical component and the one most closely tied into your ego and personal pride were the speakers you selected. Which ones did you pick? How did they stack up to your friends’ speakers?

I’m from the New England area, so in the early 1970’s, three speaker brands dominated the stereo landscape: Advent, KLH and AR. They each had their proponents and detractors, they each had very distinct tonal and spectral “personalities,” and the various stores either pushed or disparaged the different brands. One thing we’d do was engage in audio battle with each other. Someone would drag their speakers over to their friend’s parent’s house (or if it was during the college school year, over to their friend’s dorm room) and we’d set them up, side by side, each set connected to the A and B terminals of the receiver or integrated amp. Then we’d play record after record, switching from A to B, comparing bass, clarity, tonal color, high frequency extension, inner detail, you name it. We’d argue and fight:

“That’s so phony and fake sounding, so colored and exaggerated.”

“You’re nuts—yours are so dull and lifeless, so muffled, so boring. If that’s ‘accurate,’ I don’t want accuracy.”

Invariably, there would be 3rd parties in the room as well, people who didn’t own the speakers under test. The combatants would try to enlist their support and endorsement: “You hear that, right? The Advents are better, right? You agree, don’t you?”

And so it would go, often for hours. It could get quite heated and no one ever—ever—admitted that the other person’s speaker was better. Friendships could be strained during these contests and it wasn’t unusual for one person to seek out a magazine test report—days or even weeks later— that extolled the virtues of their speaker and wave that magazine in the other person’s face. “See? You’re wrong! Even Stereo Review thinks mine are the best.”

People don’t do that these days. But they sure did in the 1970’s. Stereo was really, really important and an awful lot of your personal image and pride was wrapped up in your stereo system.

Personal Aside-1

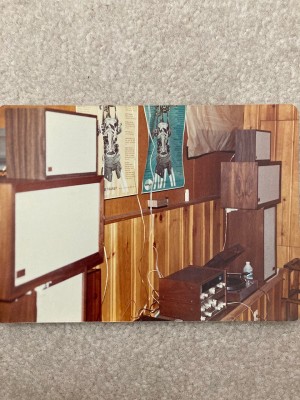

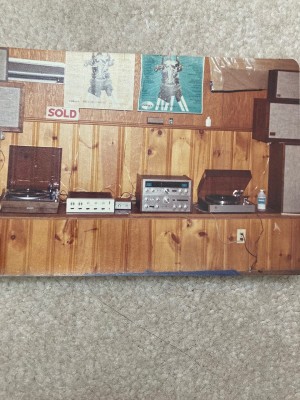

In 1973, I was 19 and totally “into” stereo gear. Lost beyond control. This was the basement of my parents’ house. On the bench is my system: The Kenwood KA-7002 integrated amplifier and matching KT-7001 tuner. To the right is my turntable, a Phillips 202 manual with a Shure V15 III cartridge. Sharp eyes will notice the Discwasher on the ledge directly above the Kenwoods and the bottle of rubbing alcohol to the right of the Phillips turntable that I used with a genuine horsehair artist’s brush to clean the stylus.

To the left of the Kenwoods is the EVX-4 4-channel adapter feeding my Dynaco SCA-80 integrated amplifier. The EVX-4 synthesized two rear ambient channels from ordinary stereo LPs.

My speakers were AR-2ax’s (10-in 3-ways), the ones sitting vertically directly on the bench. Lying horizontally on top of them are my cousin’s AR-3a’s (12-in 3-ways), which he had loaned me for a few weeks. Sitting on top of the 3a’s are my sister’s AR-7’s (8-in 2-ways), which had just arrived by mail order and I hadn’t yet brought them over to her house to set them up.The Kenwood KA-7002 had A, B and C speaker terminals, so I could switch at will between all three. What fun! The AR-7’s were AR’s smallest and least expensive speaker. The 3a was their top of the line. All three were very highly rated, with great test reports from all the major magazines. The amazing thing was how similar the 7 sounded to the 3a, except for the deepest bass and extreme highs.

Not shown in these pics are another set of AR-2ax’s connected to the Dynaco amp that comprised the rear channels of my “4-channel” stereo music system. That’s my sister’s Dual 1215 on the left, connected to the phono input of the Dynaco, again before I took it over to her place to set it up. This was my “stereo life” in the 1970’s.

Personal Aside—2

My dad was an avid audiophile, from way back. He’d jumped on the “Hi-fi/stereo” bandwagon in the 1950’s and assembled a very nice stereo system as soon as ‘stereo’ became a thing in 1958. When the 1970’s receiver power race came on, he wanted one. Really bad. He had a Sherwood S-7900A, which was a typically excellent ‘70’s receiver, 60+60 watts RMS, well-built, nice-looking. But he wanted a big one, 100+ watts per channel.

I was a sales rep in the electronics industry at the time. Our biggest line was Sanyo, which was a major brand in the 70’s and 80’s. They’ve since disappeared from the U.S. market, but they were a really big deal back then. Sanyo offered a full range of consumer electronics, like TVs, tape recorders, car stereo, compact home stereo, boomboxes, etc. They also had a hi-fi division and marketed some really excellent equipment, including receivers, turntables and cassette decks. Since I worked for the company that repped them, I could get their products at a “deal.”

So I surprised my dad with a Sanyo JCX-2900 receiver on his birthday. The Sanyo 2900 was pretty much a blatant copy of Pioneer’s SX-1050 (120 WPC, silver faceplate, amber back-lit dial, tone control turnovers, etc.), but it was a really good copy. It looked great, it had all the bells and whistles and it performed like a champ. My dad used it for many years without a hitch. He eventually upgraded several years later and gave the 2900 to a nephew of his, who used it for at least another five years.

Sanyo JCX-2900

A Decade Like No Other

So, to recap, the 1970’s were a time when so many socio-economic and technology factors came together in a way that will never be repeated:

- The Baby Boomer generation was the largest demographic group in the country’s history, and they were primed and conditioned to be voracious consumers by parents who’d lived through the Great Depression and World War II and were determined that their children would have the opportunities that they never had.

- Technology developed in such a way that great-sounding compact bookshelf speakers, reliable, high-performance receivers and integrated amplifiers, cassette recorders with Dolby B noise reduction and superb, dependable turntables all became widely available at affordable prices at the same time. What were the odds of so many unrelated technical advances-electrical, mechanical, acoustic—occurring at pretty much the exact same time?

- Popular music, fueled by the existence of the huge population pool of Baby Boomers, produced more amazingly great bands in wildly different musical genres (heavy metal/hard rock, country rock, singer/songwriter/acoustic, jazz-rock like Chicago/BST, fusion, Latin-flavored rock, soul/funk, etc.) than at any other time in our collective musical history.

- To meet this demand, stereo stores, record stores and concert venues were everywhere. Everywhere. Each weekend brought another live concert for the ages. All week after that, record and equipment sales would be off the charts.

Every time period has its charms, its special appeal. Today’s best Home Theater systems present an audio/visual experience that is far superior to what the great majority of commercial theaters can offer in return. But the visceral emotion surrounding the acquisition and ownership of today’s gear is not anywhere near what it was like 50 years ago. No present-day AV enthusiast puts a friendship in jeopardy by arguing about their speakers vs. their friend’s, and then goes and derisively waves a magazine test report under their friend’s nose and says, “See?” That kind of raw excitement, that defensive pride in one’s meticulously selected system, fueled by out-of-control 18-22 year-old emotions, was strictly a 1970’s singularity.

It’ll never be that way again. But for those of us who lived it, it was fun on a scale not even remotely approached by today’s electronics market.