History of Surround Sound Processing: The Battle for Dolby Pro Logic II

originally published: March 03, 2015

This article is republished in memory of Jim Fosgate who recently passed away on December 9th, 2022. A true industry icon is gone but NOT forgotten. This article is a historical account of the battle for Dolby Prologic II and Jim's involvement with the development of a revolutionary surround upmixer and it's impact on home theater.

The development of pre-digital surround sound through the experiences of someone who was there for a big chunk of it…

Surround Sound Upmixer History Youtube Discussion w Roger Dressler

It was 1971 when I decided to upgrade my audio system from an 18-watt Knight integrated tube amplifier to a Dynaco SCA-80Q integrated, in kit form. I preferred assembling my audio electronics, more for the aesthetics than anything else. Despite the glowing reviews you can find online extolling the natural, powerful performance of this amplifier, it was a fairly pedestrian piece.

Dynaco SC-80Q 4CH Amp

I had this setup for about a year before I tried an unused feature of this Dynaco amplifier; Dynaquad. This simple passive matrix was based upon a Hafler circuit that retrieved ambience and simulated “quad” by sending information through additional amplifier channels to two more speakers. It was a bit unnatural and gimmicky, but I was mesmerized by the effect.

Eventually, my SCA-80Q failed rather dramatically one evening, with a loud “POP!” accompanied by a bright flash, a mini-mushroom cloud, and, finally, the familiar aroma of burnt carbon. I replaced the charred amp with a Crown IC-150 preamp (famously known as “a straight wire with grain”) and a Phase Linear 400 power amp. It was a significant sonic improvement, and I completely forgot about 4-channel sound…for the time being.

I retired as a professional drummer on New Year’s Eve, 1978-1979, finishing the last night I would be paid to play drums with a raucous ten-minute solo. The band packed up all the gear on that snowy early Chicago morning, and a day later, I was the manager of a suburban Chicago audio/video store, wearing a tie, and feeling severely disoriented. It was my love of hi-fi that fostered my love of music, and things had come full circle. I was now selling hi-fi; Yamaha, Nakamichi, Gale, Dahlquist, McIntosh, Revox, B&O.

The Audionics Space & Image Composer was conceived in 1976, and was produced from 1979 to 1980, when the Tate chipset supply was exhausted.

A year into my new career, a rep brought in an array of electronic components from a small company known as Audionics of Oregon. There were three components; the BT-2 preamp, the CC-2 power amp, and a peculiar piece with the esoteric moniker “Space & Image Composer.” While glancing at the front panel, I noticed an SQ control, and my eyes lit up: Quad!

Quad was about dead by this time (1980), but this interesting device did something far better than decode SQ. It could generate four discrete channels from any two-channel source, and the effect was dramatic. Every record (or soon, CD) in one’s collection was now 4-channel. I sold almost two dozen systems using the Space & Image Composer with accompanying Audionics amps and a preamp, to the delight of my customers. All of them ran out to buy “Dark Side of the Moon” and “Crime of the Century.”

Charles Wood was the president of Audionics of Oregon, and we quickly hit it off. We are close to this day. The Audionics of Oregon Space & Image Composer was one of the world's first two commercially available SQ/Surround processors utilizing the Tate Directional Enhancement System. The key phrase was “surround processor.” It was an active-matrix device, with steering logic based upon the Tate chipset, which is long extinct. The effect was far more dramatic than Dynaquad or Hafler technology, because those were passive matrix designs that were very simple, and they pretty much just extracted ambience and directed it to the rear. The Tate chipset actually would pull hard left and hard right sounds in the mix to the side or rear creating an unnerving, discrete 4-channel sound.

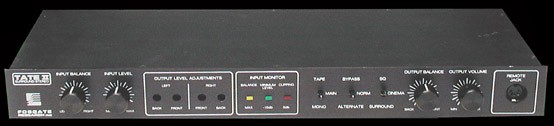

Coincidentally, another industry visionary, Jim Fosgate, had developed a processor at the same time, the Tate 101. It used the same chipset, offered about the same performance as the Composer, and it was priced about the same; around $1,100. In the mid-1980s, Audionics of Oregon was absorbed by Fosgate, and the company Fosgate-Audionics was born in Heber City, Utah. Jim Fosgate continued developing and perfecting his own surround technologies, surpassing what the Tate technology could do. Charlie Wood joined Jim as his sales manager, marketing manager, PR person, etc. They designed, manufactured, and sold surround products in a modest facility in quaint Heber City.

I stayed in touch with Charlie Wood through this period, speaking with him at least once a month. We would trade war stories, and he often said he wished he could divest himself of sales responsibilities to concentrate on marketing, product development, and “not talking to people on the phone.” During an especially nightmarish retail day, Charlie called me and asked if I wanted to be a national sales manager. I jumped at it. A few days later, I made a non-stop 21-hour drive from Chicago to Heber City and interviewed for the job. I gave my 3-month notice at Columbia Audio Video and in 1989, we moved to Utah.

During the 1980s, surround sound really came into its own, primarily used for VHS soundtracks. Dolby Surround was a passive matrix, like the Hafler circuit, and it placed ambient mono information in either one or two rear speakers. (Dolby Stereo was a crude active matrix pro surround technology used in theaters.) Because separation was only about 3 dB (front to back) with Dolby Surround, front channel information in the rear channels was subdued by rolling the highs off. Dolby Pro Logic was introduced in 1986, and it used an active matrix, with slow steering logic and processing. However, unlike the Fosgate and Audionics pieces that had already been around for seven years, Pro Logic had a mono rear channel that was also bandwidth limited to 7 kHz. To remove unwanted artifacts, Dolby threw the baby out with the bath water. By focusing on eliminating artifacts, detail, speed, and separation were compromised. Jim Fosgate’s designs used full-range, stereo rear channels, the control voltages were such that attack and release times were much faster, and Jim continuously toiled to eliminate the audible artifacts such as pumping, breathing, random glitches, etc. We honestly felt our little-known technology was superior to the industry standard, Dolby Pro Logic. At this same time, Lexicon had developed very robust surround processors using Pro Logic that they had cleverly implemented in the digital domain. Lexicon was Fosgate’s main competition, and their products were solid. My arch-rival at the time was my friend Buzz Goddard, an industry icon even today. If you bought a high-end surround preamp in 1990, it was most likely either a Fosgate-Audionics or a Lexicon.

Jim Fosgate's Tate 101a was developed in parallel to the Audionics Space & Image Composer, and they were the first two commercially available active-matrix surround processors.

At this time, Fosgate-Audionics had a who’s who of surround sound giants working in our modest facility. In addition to surround legends Charlie Wood and Jim Fosgate, we also had Martin Wilcox. Martin had worked for Wes Ruggles who started Tate Audio. CBS provided some early funding to Tate because they recognized it was superior technology to CBS’ own SQ steering logic developed at CBS Labs. Bob Popham implemented many of Jim’s designs, and he was invaluable at Fosgate-Audionics. Bob previously worked for Audionics of Oregon as a teen, and he is still repairing vintage units at his shop in Grand Junction, Colorado.

We rolled out new surround processors, and eventually, the Fosgate Audionics THX System, which may have been the first audiophile-quality complete THX system, including processor, amps, dipole surrounds, and subs. The speaker system was designed for us by the legendary John Dunlavy, a truly nice man who knew how to design great speakers.

The company was cooking. And then due to poor cashflow because of exploding sales…we ran out of money. This is common with businesses that are under-funded and grow too quickly. Jim’s wife Norma and her daughter Lezlee Cameron did a masterful, courageous juggling act with the finances to keep the company alive.

Charlie, Jim, and I scrambled to find a big company to rescue us, and it came down to Rockford Corporation, Harman International, or International Jensen. It was Martin Wilcox who had a contact at Harman. My last choice was Harman, based upon how other small companies had fared, and sure enough, they acquired us. The experience wasn’t bad, though, because the Harman person who became our boss was the bright, hilarious, and very human Michael Heiss.

As I had anticipated, other than Mike Heiss, our corporate overlords couldn’t grasp what we were doing. They downsized the company to a handful of people, moved production to a large Utah facility that had never manufactured products this complex, and our business was disrupted and in disarray. It was then that Dr. Harman, a man I liked and respected a great deal, decided that the accolades Fosgate-Audionics was getting should be awarded to a company with more of a Harman lineage. The name Fosgate-Audionics was retired, and new products were launched under the Harman Kardon Citation name.

The new Citation electronics—a premium processor and two multi-channel amplifiers—were exquisite, performed well, and sounded quite good. But the real star was Jim’s newest incarnation of his surround technology, 6-Axis. It worked almost flawlessly. With attack and release times as much as 100 times faster than Pro Logic, full-range rear channels, freedom from artifacts, and superb fidelity, Jim Fosgate had hit it out of the park. Not only was it very effective on movie soundtracks, 6-Axis added a new dimension to listening to music, and it almost replicated quad from a stereo source. This was also a period in time when most surround enthusiasts (and the Dolby folks) realized that Dolby Pro Logic was long in the tooth and needed an upgrade.

The Citation 7.0 preamp/processor was the first audio component to use Jim Fosgate's propriotary 6-Axis processing, which was the precursor to Dolby Pro Logic II.

Another one of Harman’s acquisitions was Lexicon, a highly respected name in the pro business as well as in the consumer market. Their processors were very good, but they were stuck with the aging Pro Logic. They were, however, developing a new surround technology, Logic 7, a product of the brilliant David Griesinger. Harman now had the two leading alternatives to replace Dolby Pro Logic, and Harman executives in sales and engineering became divided on which one would emerge, if in fact either would. As time went on, it started to look as if Logic 7 would become Pro Logic II, due to a higher level of support within Harman. Jim and his technology were being viewed as superfluous.

Assuming that

Logic 7 would win, Harman management did something that in retrospect was

unwise. Jim Fosgate was terminated. Wisely, he exempted and retained the rights

to some key patents he felt would be useful in the future, and he was correct.

Charlie Wood offers a first-hand explanation: “Post Harman, Jim continued to

work on the technology and evolve what was 6-Axis, employing the patent rights

he withheld. Jim and I got Roger Dressler of Dolby Laboratories over to hear

what Jim had developed. Roger returned to Dolby and convinced others there,

including Ray Dolby, that Jim’s technology was superior and that if Dolby tried

to re-invent it to avoid patent infringement that it would be a futile effort.

Dolby then signed a generous licensing agreement with Jim and made his 6-Axis

system the new Dolby Pro Logic II. That development made him a wealthy

man, with over 300 million pieces of gear produced worldwide with his Pro Logic

II and IIx technology incorporated within…”

Assuming that

Logic 7 would win, Harman management did something that in retrospect was

unwise. Jim Fosgate was terminated. Wisely, he exempted and retained the rights

to some key patents he felt would be useful in the future, and he was correct.

Charlie Wood offers a first-hand explanation: “Post Harman, Jim continued to

work on the technology and evolve what was 6-Axis, employing the patent rights

he withheld. Jim and I got Roger Dressler of Dolby Laboratories over to hear

what Jim had developed. Roger returned to Dolby and convinced others there,

including Ray Dolby, that Jim’s technology was superior and that if Dolby tried

to re-invent it to avoid patent infringement that it would be a futile effort.

Dolby then signed a generous licensing agreement with Jim and made his 6-Axis

system the new Dolby Pro Logic II. That development made him a wealthy

man, with over 300 million pieces of gear produced worldwide with his Pro Logic

II and IIx technology incorporated within…”

I would have felt schadenfreude towards those at Harman who leveraged so hard for Logic 7, except they are good, talented people, and many are still friends of mine. Logic 7 would have made a good Pro Logic II, but for the decades and decades of tireless work without reward that Jim put in, he definitely earned it

A few years later, Jim Fosgate and Charlie Wood were reunited with Rockford Corporation, and a new surround preamp was launched. I was given two beta versions for evaluation, and it was a nice piece, but the reality was Jim had little to do with it. It was virtually the same as an Outlaw processor, with no proprietary circuitry to distinguish it as far as I know. A few of us contributed marketing suggestions which were ignored, and the brand died, and with it, the name Fosgate-Audionics.

The End of an Era?

We all knew that at some point in time, digital implementations of surround sound would replace the analog versions, and that PLII was a stopgap before the demise of analog surround. Once in a while, I’ll still use Pro Logic II or Pro Logic IIx to watch a movie, and the sound and imaging are pretty close to Dolby Digital, despite much shallower separation. Television programs that are broadcast in stereo automatically switch to PLIIx in my surround preamp. And although I usually listen to music in pure stereo, there are recordings that come alive when played in Pro Logic II Music mode. As with all other developing technologies, digital surround has eclipsed analog surround and will someday replace it entirely. I am not so eager to see that happen.

Did Dolby made the right choice for Pro Logic II? Please participate in our Dolby Pro Logic II forum discussion and let us know what you think.